Title: Songwe River to Kigali (Rwanda)

Dates: 27th May to 8th June GPS:

Distance: 1385km Total Distance: 17,068km

Roads: 873km gravel, sand; 512km tarmac – high mountains, long climbs, rolling hills in central Tanzania

Weather: high 20s, early 30s, prevailing easterly winds (cross winds)

Finally I have managed to draw a new route map which shows the first 17,000km of the journey. Please click on the adjacent icon to see an accurate representation of the route so far (up to Kigali). Entering Tanzania, we moved forward into another time zone – we’re now only 7 hours behind Eastern Standard Time in Australia (and just 5 hours behind WA). The first day in Tanzania was all about sucking in as much air as possible and absorbing a new culture as I cycled from about 500metres near Lake Malawi to 2300metres before dropping back to 1700metres at Mbeya. Initially the road ascended through some wild jungle-like terrain, away from the lake and into the low-level clouds. I saw two troops of monkeys beside the road and stopped to try to film some of them. This wasn’t that easy because they always try to hide by keeping leafy branches in their line of view.

Finally I have managed to draw a new route map which shows the first 17,000km of the journey. Please click on the adjacent icon to see an accurate representation of the route so far (up to Kigali). Entering Tanzania, we moved forward into another time zone – we’re now only 7 hours behind Eastern Standard Time in Australia (and just 5 hours behind WA). The first day in Tanzania was all about sucking in as much air as possible and absorbing a new culture as I cycled from about 500metres near Lake Malawi to 2300metres before dropping back to 1700metres at Mbeya. Initially the road ascended through some wild jungle-like terrain, away from the lake and into the low-level clouds. I saw two troops of monkeys beside the road and stopped to try to film some of them. This wasn’t that easy because they always try to hide by keeping leafy branches in their line of view.

It started to rain heavily as I worked my way slowly up through some extensive tea plantations. Land use from then on became intensive with a variety of vegetables and fruit being grown on terraced plots and for sale beside the road. I was sodden by lunchtime (70km) and so John made soup to warm me up – and to go with the “Obama Buns” he had found in a small bakery. President Obama is a very popular man across Africa, but seems to be even more so as we near Kenya his country of birth. In Mali we saw “Obama” perfume in a store in the town of Nara. I’ve noted children wearing Obama t-shirts in most countries and we see Obama posters everywhere. The Obama buns were actually excellent – very sustaining.

Near the summit I met a German cyclist, Ingor – another tourist riding to the World Cup in South Africa. He didn’t think he would make it to the first match which he reminded me was against Australia. I reminded him not to be too cocky about the match… In Mbeya, John checked with truck drivers who had recently travelled or knew about the route we planned to take through to Tabora. The word generally seemed to be that it was passable for a LandRover, but not a two-wheel drive vehicle. We had been worried about all the rain we were having around Lake Malawi, but the lake creates its own weather pattern and the high mountains form a barrier to the weather. Once over the next huge pass out of Mbeya, we would enter a rain shadow – dropping down to the high central plains. We decided to go for it. The route would be much shorter and I was eager to venture along this little travelled road through central Tanzania.

Near the summit I met a German cyclist, Ingor – another tourist riding to the World Cup in South Africa. He didn’t think he would make it to the first match which he reminded me was against Australia. I reminded him not to be too cocky about the match… In Mbeya, John checked with truck drivers who had recently travelled or knew about the route we planned to take through to Tabora. The word generally seemed to be that it was passable for a LandRover, but not a two-wheel drive vehicle. We had been worried about all the rain we were having around Lake Malawi, but the lake creates its own weather pattern and the high mountains form a barrier to the weather. Once over the next huge pass out of Mbeya, we would enter a rain shadow – dropping down to the high central plains. We decided to go for it. The route would be much shorter and I was eager to venture along this little travelled road through central Tanzania.

I was looking forward to tackling the first obstacle – the high pass dividing Mbeya from Chunya – and had psyched myself accordingly. There was no warm up climb – it was simply straight up out of the town. I immediately dropped into the lowest range of gears. The path was extremely steep and stony, so it was a matter of focusing on just in front of the wheel to keep upright.

When I did have the opportunity to look up, the views were exceptional. Mbeya, one of Tanzania’s largest towns, gradually shrunk to appear as an insignificant mark within the immense scale of the valley. I felt extremely satisfied reaching the pass; a sign reminding me that it was the country’s highest trunk road. Whoever wrote the sign was about 500metres too generous with the altitude though, saying it was 2916metres rather than the 2466metres displayed on John’s GPS. The road then wound a convoluted path along a ridge, staying above 2000metres for at least 20km, before dropping down through some treacherous patches of bulldust and on to Chunya.

When I did have the opportunity to look up, the views were exceptional. Mbeya, one of Tanzania’s largest towns, gradually shrunk to appear as an insignificant mark within the immense scale of the valley. I felt extremely satisfied reaching the pass; a sign reminding me that it was the country’s highest trunk road. Whoever wrote the sign was about 500metres too generous with the altitude though, saying it was 2916metres rather than the 2466metres displayed on John’s GPS. The road then wound a convoluted path along a ridge, staying above 2000metres for at least 20km, before dropping down through some treacherous patches of bulldust and on to Chunya.

The following day was marred by slow punctures and a leaking oil seal on John’s rear axle and so we lost time attending to the breakdowns. Punctures are simple to fix, but the LandRover’s problem was potentially serious if John didn’t attend to it straight away. Replacing the seal was a fiddly job in the bush amongst accumulating numbers of sweat bees. Not too much time was lost however and I still clocked 106km, finishing in the dark.

Sunday 30th May started alright and I enjoyed passing through a string of small villages. Then it all started to become heavy going as the path became sandy, especially along the low points. That wasn’t the worst of it though – just as I was struggling through deep sand I was bitten again and again by tsetse flies. Pretty soon a large angry swarm of tsetse hovered around and behind me. My clothes gave no protection. They could bite through my cycle shorts, shirt, gloves and socks. The bites are sharp and painful – sometime deep enough to draw blood. Give me the good ol’ Aussie fly any day. Australian bush flies are just annoying, and during my Australian expedition, once I generated some speed and brushed my shirt a few times I could lose them.

Sunday 30th May started alright and I enjoyed passing through a string of small villages. Then it all started to become heavy going as the path became sandy, especially along the low points. That wasn’t the worst of it though – just as I was struggling through deep sand I was bitten again and again by tsetse flies. Pretty soon a large angry swarm of tsetse hovered around and behind me. My clothes gave no protection. They could bite through my cycle shorts, shirt, gloves and socks. The bites are sharp and painful – sometime deep enough to draw blood. Give me the good ol’ Aussie fly any day. Australian bush flies are just annoying, and during my Australian expedition, once I generated some speed and brushed my shirt a few times I could lose them.

Tsetse however appear to be the athletes of the fly world. Even at 40km per hour, they would easily keep up – I could not lose them. John cycled out to meet me before the end of the first session and he too was attacked. They seemed to disappear in any inhabited area. When we stopped moving, they would soon lose interest and disappear. The trouble was that I had to cycle eight hours a day. For two days that meant I was continually attacked and found myself cycling faster and faster to try and get rid of them – to no avail.

There were few villages marked on our map, but one was Kipembawe. We had expected to find the usual string of shops with little to buy and people milling around, chatting, selling from roadside stalls. Kipembawe was different though. It was completely dead – a ghost town. We never managed to confirm what we deduced from looking at the deserted buildings. A series of houses lined an overgrown street. They were solid well-made brick structures.

There were few villages marked on our map, but one was Kipembawe. We had expected to find the usual string of shops with little to buy and people milling around, chatting, selling from roadside stalls. Kipembawe was different though. It was completely dead – a ghost town. We never managed to confirm what we deduced from looking at the deserted buildings. A series of houses lined an overgrown street. They were solid well-made brick structures.

The date 1945 was painted on one facade and serial numbers branded each house. We think it was some sort of military outpost built at the end of the Second World War. By whom, we don’t know and no one seemed to know much about it. It was strange that it was deserted as usually in other places we have visited, locals would have moved into the houses or at least reuse all the materials.

The date 1945 was painted on one facade and serial numbers branded each house. We think it was some sort of military outpost built at the end of the Second World War. By whom, we don’t know and no one seemed to know much about it. It was strange that it was deserted as usually in other places we have visited, locals would have moved into the houses or at least reuse all the materials.

The tsetse problem worsened on second day. I started the day wearing a thick cotton long sleeved shirt which also protected my backside a little. They bit straight through that so I added a cycle jersey under it. The double layer of clothing worked, but they just concentrated on other body parts, especially my hands and the backs of my legs. Next I added a waterproof jacket and wrapped the shirt around my waist – a little better. Heading north from the remote village and mission of Kitunda, the problem worsened to a new level. I was travelling under a cloud of thousands of aggressive flies.

The tsetse problem worsened on second day. I started the day wearing a thick cotton long sleeved shirt which also protected my backside a little. They bit straight through that so I added a cycle jersey under it. The double layer of clothing worked, but they just concentrated on other body parts, especially my hands and the backs of my legs. Next I added a waterproof jacket and wrapped the shirt around my waist – a little better. Heading north from the remote village and mission of Kitunda, the problem worsened to a new level. I was travelling under a cloud of thousands of aggressive flies.

My barbag was coated with a thick mass of flies. (In the picture you see, I had tipped many of them off the barbag to retrieve my camera. I had to endure plenty of bites while I took the photo. John said that they would sit on the spare wheel of the vehicle and some would even keep speed as he drove, so he had to keep the windows closed. After lunch I resorted to desperate measures. My full suit of armour included; thick socks, double-lined track bottoms with a pair of cycle shorts over the top, cycle jersey and waterproof jacket, winter gloves, tape around my wrists because they kept finding the gap between glove and jacket, scarf, insect head net. It kept out the flies but was extremely hot. Nevertheless it was relief. There was a lot of sand and a few testing rough patches to endure too, but at least I could relax a little.

My barbag was coated with a thick mass of flies. (In the picture you see, I had tipped many of them off the barbag to retrieve my camera. I had to endure plenty of bites while I took the photo. John said that they would sit on the spare wheel of the vehicle and some would even keep speed as he drove, so he had to keep the windows closed. After lunch I resorted to desperate measures. My full suit of armour included; thick socks, double-lined track bottoms with a pair of cycle shorts over the top, cycle jersey and waterproof jacket, winter gloves, tape around my wrists because they kept finding the gap between glove and jacket, scarf, insect head net. It kept out the flies but was extremely hot. Nevertheless it was relief. There was a lot of sand and a few testing rough patches to endure too, but at least I could relax a little.

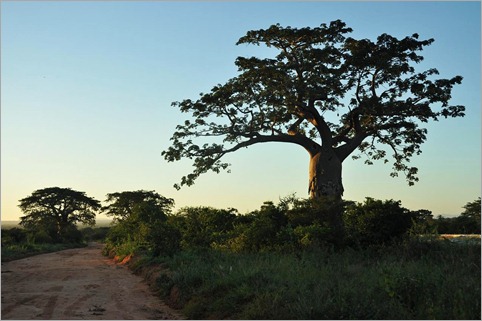

Despite the discomfort, we were travelling through a beautiful wild place with no people around – not even a car passed during the night. Setting off the next morning I was prepared for another battle with the tsetse, but it never eventuated. Just as fast as they descended upon us, they disappeared. I noted on the map that we had been travelling across the same latitude as when we encountered the tsetse in Angola, although the problem in Angola was only for about 40km and less intense than in Tanzania. About a kilometre from our campsite John noticed some lion footprints.

Despite the discomfort, we were travelling through a beautiful wild place with no people around – not even a car passed during the night. Setting off the next morning I was prepared for another battle with the tsetse, but it never eventuated. Just as fast as they descended upon us, they disappeared. I noted on the map that we had been travelling across the same latitude as when we encountered the tsetse in Angola, although the problem in Angola was only for about 40km and less intense than in Tanzania. About a kilometre from our campsite John noticed some lion footprints.

Tabora was a big friendly, relaxed African town. We enjoyed a day off there catching up on internet connections and bits and pieces. We’d been led to believe that that was the end of the rough unsealed road and so John switched tyres back to efficient road tyres. Six kilometres out of town however I was back on the dirt. It was heavy going for another day and a half before we finally rejoined the tarmac. Our next major concern was security between Kahama and the Rwandan border.

Even a fellow in a small village, 15km before the bitumen warned that the region after Kahama was still full of refugees who fled from Burundi and Rwanda during and after the genocide. John quizzed a few truckies and learned that the real danger of being ambushed and robbed was after dark, so we proceeded with caution ensuring that we reached the safety of a hotel. This meant lopping off a couple of hours at days end to ensure we were set up before dark.

Even a fellow in a small village, 15km before the bitumen warned that the region after Kahama was still full of refugees who fled from Burundi and Rwanda during and after the genocide. John quizzed a few truckies and learned that the real danger of being ambushed and robbed was after dark, so we proceeded with caution ensuring that we reached the safety of a hotel. This meant lopping off a couple of hours at days end to ensure we were set up before dark.

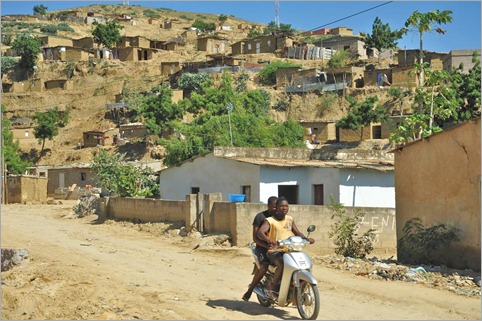

As we neared Rwanda, the land became very hilly and I was slowed up by a few long climbs. Rwanda is known as “Land of a Thousand Hills”, so I was expecting some hard work. Across the border at Rusumo (spectacular waterfall), many things changed dramatically. It was back to driving on the right hand side of the road. There were a lot more people. Rwanda is a tiny landlocked country with a population of 11 million. Rather than one cyclist joining me at a time, it was more like a peloton.

There were plenty of smiling faces and every time I stopped I was mobbed by a crowd of inquisitive children. There are no plastic bags in Rwanda and the streets are free of litter. Village main streets were clean and tidy with rubbish bins and gardens. There has been a lot of aid money pumped in to Rwanda to help citizens recover from the horrors of the genocide when at least two-thirds of the population were displaced and one million killed.

We made good time to reach Kigali a day early. Zdenek flew in on 9th June to rejoin the expedition. Our main goals were to visit the Millennium Village of Mayange, just south of the beautiful city and learn more about the genocide and how the nation is coping 16 years on.

{ 6 comments }

from Livingstone, I was very pleased. It was well worth the effort. Mac is a great character and his bar/restaurant is also brimming with atmosphere. If you like huge meals of steak, chicken or mixed grills with fried eggs and chips – then MacRon’s is for you. We were spoilt with the hugest meals which barely fitted on the enormous plates, balanced with a small token pot of coleslaw each. We watched a Super 14s rugby encounter with Mac and his other clients; Mac providing the meal and extra rounds of drinks on the house.

from Livingstone, I was very pleased. It was well worth the effort. Mac is a great character and his bar/restaurant is also brimming with atmosphere. If you like huge meals of steak, chicken or mixed grills with fried eggs and chips – then MacRon’s is for you. We were spoilt with the hugest meals which barely fitted on the enormous plates, balanced with a small token pot of coleslaw each. We watched a Super 14s rugby encounter with Mac and his other clients; Mac providing the meal and extra rounds of drinks on the house. Zambia has a real cycling culture and many cyclists, especially boys and teenagers like to try to race me. Normally they amble along and so I pass them just going my usual pace. They respond with a burst of speed – not sustainable – and leave me in their wake. Once they have beaten me, the incentive is gone and their effort soon fizzles out. Their bikes are usually held together with whatever they can find, have pedals missing, buckled wheels, broken seats…and they are often carrying huge loads. On the final morning in to Lusaka, another young man zoomed passed me as I cycled through Kafue. As we hit the hill out of town, he struggled on his single geared machine and I caught him. We rode together for about 20km and had a great conversation while others followed for short distances and then peeled off. His name was Steve. I thought he looked about 15, but he said he was 12, although in year 9 at school. He seemed a very bright kid and said he wanted to be a lawyer when he grew up. Steve’s father died in 2006, I think from AIDS. His mother is a farmer and has to care for her ten children. She grows maize and sugar cane to sell to a local cooperative, but struggles to make ends meet. Steve said he was cycling to visit a friend just outside Lusaka but I thought he should have been at school, so I asked why. He explained that he hasn’t been able to go to school for the last month because his mother can’t afford the school fees. When the LandRover caught us I gave him something to eat and water. We made a few small improvements to the bike, Dan repositioning a piece of wood to stop the mudguards rubbing through the tyre.

Zambia has a real cycling culture and many cyclists, especially boys and teenagers like to try to race me. Normally they amble along and so I pass them just going my usual pace. They respond with a burst of speed – not sustainable – and leave me in their wake. Once they have beaten me, the incentive is gone and their effort soon fizzles out. Their bikes are usually held together with whatever they can find, have pedals missing, buckled wheels, broken seats…and they are often carrying huge loads. On the final morning in to Lusaka, another young man zoomed passed me as I cycled through Kafue. As we hit the hill out of town, he struggled on his single geared machine and I caught him. We rode together for about 20km and had a great conversation while others followed for short distances and then peeled off. His name was Steve. I thought he looked about 15, but he said he was 12, although in year 9 at school. He seemed a very bright kid and said he wanted to be a lawyer when he grew up. Steve’s father died in 2006, I think from AIDS. His mother is a farmer and has to care for her ten children. She grows maize and sugar cane to sell to a local cooperative, but struggles to make ends meet. Steve said he was cycling to visit a friend just outside Lusaka but I thought he should have been at school, so I asked why. He explained that he hasn’t been able to go to school for the last month because his mother can’t afford the school fees. When the LandRover caught us I gave him something to eat and water. We made a few small improvements to the bike, Dan repositioning a piece of wood to stop the mudguards rubbing through the tyre. I cycled about 4km with the two girls back to Evelyn’s village to meet her family. We were also joined by Joyce, the religious education teacher. Once I could get some momentum, the bike seemed to handle even the sandy patches with ease. Evelyn’s mother has five children and is alone. Her husband died a few years ago (we suspect of AIDS, but not 100% sure) and so she did everything; grew maize, sugar cane, pumpkins and onions, she baked bread and sold her produce at the local market, brought up the family and is a care worker. In fact she qualified for a bicycle through the RAPIDS program a couple of years ago.

I cycled about 4km with the two girls back to Evelyn’s village to meet her family. We were also joined by Joyce, the religious education teacher. Once I could get some momentum, the bike seemed to handle even the sandy patches with ease. Evelyn’s mother has five children and is alone. Her husband died a few years ago (we suspect of AIDS, but not 100% sure) and so she did everything; grew maize, sugar cane, pumpkins and onions, she baked bread and sold her produce at the local market, brought up the family and is a care worker. In fact she qualified for a bicycle through the RAPIDS program a couple of years ago. initiative. Muna and Irene, project coordinators, took us to see Jennifer. Like Evelyn’s mother, Jennifer already leads a full life let alone volunteering to care for 28 people on a regular basis. She received her training back in 2006, which included a basic medical kit and counselling instruction. Carers like Jennifer are their community’s first port of call if someone needs help. If someone needs more serious medical attention, she can refer and encourage them to get to a hospital. Using her bicycle, Jennifer is able to attend more patients more often and give more quality time than if she was on foot. The bicycle has increased her productivity immensely. She has also improved her own economic circumstances. One of Jennifer’s patients lived next door, (many are much further away) so she took us to meet Emma. Irene explained that Emma nearly died of AIDS. Unable to eat because of the sores on her throat, she had almost gone when they took her to be diagnosed and receive treatment. Now she can have a productive life again, even starting to work in the fields thanks to the right ARV medication. Jennifer still cares for her as a home help. Emma was joking and upbeat and it was wonderful to see how she was able to contribute to her family and community again.

initiative. Muna and Irene, project coordinators, took us to see Jennifer. Like Evelyn’s mother, Jennifer already leads a full life let alone volunteering to care for 28 people on a regular basis. She received her training back in 2006, which included a basic medical kit and counselling instruction. Carers like Jennifer are their community’s first port of call if someone needs help. If someone needs more serious medical attention, she can refer and encourage them to get to a hospital. Using her bicycle, Jennifer is able to attend more patients more often and give more quality time than if she was on foot. The bicycle has increased her productivity immensely. She has also improved her own economic circumstances. One of Jennifer’s patients lived next door, (many are much further away) so she took us to meet Emma. Irene explained that Emma nearly died of AIDS. Unable to eat because of the sores on her throat, she had almost gone when they took her to be diagnosed and receive treatment. Now she can have a productive life again, even starting to work in the fields thanks to the right ARV medication. Jennifer still cares for her as a home help. Emma was joking and upbeat and it was wonderful to see how she was able to contribute to her family and community again. The third initiative which supports economic development through micro-finance loans for bicycles seems to be the way WBR is heading – creating sustainable businesses. The WBR bikes cost around $US150 each, beyond the means for the average villager. When a person, or often a small group of people decide they have a need for a bike, they can make an appointment with the staff at Harmos, a micro-lending bank. Typically they need to contribute a third of the amount, and with a guarantee from the village headman can secure a $100 loan. The loans must be repaid within 3-6 months and currently about 89% are honoured within the time frame. I had a chat with James Phiri at the loans office,

The third initiative which supports economic development through micro-finance loans for bicycles seems to be the way WBR is heading – creating sustainable businesses. The WBR bikes cost around $US150 each, beyond the means for the average villager. When a person, or often a small group of people decide they have a need for a bike, they can make an appointment with the staff at Harmos, a micro-lending bank. Typically they need to contribute a third of the amount, and with a guarantee from the village headman can secure a $100 loan. The loans must be repaid within 3-6 months and currently about 89% are honoured within the time frame. I had a chat with James Phiri at the loans office,  who then took us to meet Joe – to showcase the initiative. Joe seems unstoppable. He used his first bike to carry charcoal to Lusaka to sell. He said this is all he did for six months – put his head down and worked. With the money he saved, he was able to buy another bike. Within two years he now has six businesses. His incentives are to plan ahead so that when he is too old to push the pedals, he has an income and his family a decent inheritance. The notion of such forward planning is rare in Joe’s culture. Joe showed how he attached the special goat cage to the carrier so he can transport his goats to market. He has bought more land on which he and his family grow vegetables to eat and sell. He rents the properties he has bought and on the day we visited he had just bought another sewing machine. He plans to employ six tailors to produce clothes. We all sat under a shady tree where initially Joe explained how with the loan giving him a leg up, he has created so much. However, when Joe learned what I was doing, roles were reversed. He asked many very thoughtful and appropriate questions. Joe is a great advertisement for the program as he tells everyone with such enthusiasm how to do what he has done. I think we inspired each other!

who then took us to meet Joe – to showcase the initiative. Joe seems unstoppable. He used his first bike to carry charcoal to Lusaka to sell. He said this is all he did for six months – put his head down and worked. With the money he saved, he was able to buy another bike. Within two years he now has six businesses. His incentives are to plan ahead so that when he is too old to push the pedals, he has an income and his family a decent inheritance. The notion of such forward planning is rare in Joe’s culture. Joe showed how he attached the special goat cage to the carrier so he can transport his goats to market. He has bought more land on which he and his family grow vegetables to eat and sell. He rents the properties he has bought and on the day we visited he had just bought another sewing machine. He plans to employ six tailors to produce clothes. We all sat under a shady tree where initially Joe explained how with the loan giving him a leg up, he has created so much. However, when Joe learned what I was doing, roles were reversed. He asked many very thoughtful and appropriate questions. Joe is a great advertisement for the program as he tells everyone with such enthusiasm how to do what he has done. I think we inspired each other!