Title: Brazzaville (ROC) to Luanda (Angola)

Dates: 26th March to 1st April GPS:

Distance: 863km Total Distance: 10,974km

Roads: 385km gravel, 478km tarmac; mix of steep hills and rolling hills

Weather: Hot, humid, some rain (typical for rainy season

Support from our friends from DMC Mining in Brazzaville extended to helping us with border formalities, crossing the mighty Congo River and seeing us off in Kinshasa. The process all seemed ridiculously complicated and basically caused us to lose a day. We were ready to go at 8am, but no one else seemed to be. It was a day of waiting. I started off from where I arrived in Brazzaville, at the Hotel Cedre. There are faster ferries but we had to put the vehicle on a slow boat – it was the only vehicle, the rest was cargo and foot passengers – hundreds of them! It was absolute chaos. People were squashed in; the disabled in roughly welded homemade mobile chairs. We saw looters going through sacks of goods, taking what they wanted and then sewing the bags up again. The boat set off half an hour late, then had to return to the Brazzaville side three times before finally making the short crossing. When the ferry docked passengers swarmed like a herd of animals crushing each other to get off. Police were heavy handed wielding their batons, beating people indiscriminately. We waited quietly to the side, except Simon who was in the vehicle, guarding our equipment.

It took another hour and a half for the authorities to process our passports and then immigration asked that we have our vehicle disinfected! After insisting on seeing the paperwork which explains that this is a ‘normal’ procedure, we had no choice but to pay $US60 to have the vehicle and my bike sprayed (haphazardly)! We were glad to get out of there! Noel, a friend of Arsene’s (DMC) met us and directed us back to his family’s little hotel, about 15km from the port. At least we had a guide to see us through Kinshasa and a safe place to keep the vehicle for the night.

Given all the travel warnings and reports of robberies, corrupt police and high prices, our objective in the Democratic Republic of Congo was to travel through it as quickly as possible. From Kinshasa it took just two days to cover almost 300km from Kinshasa to Songololo and the Angolan border. I did have the best tarmac strip in the country to savour. There was a fair amount of traffic moving between Kinshasa and the main port of Matadi; quite a contrast to the road we had experienced north of the border between Point Noir and Brazzaville. A big difference between the two countries I felt that the men were much more aggressive in general. Their general attitude did improve however on the second day once we were well away from Kinshasa. When the Simon, Dan and Zdenek stopped to ask police for directions as they did in any other country, the police asked for money. Needless to say they didn’t try that again. I also had a tricky incident with a policeman and his friends, but calmly negotiated my way out of the situation.

From Songololo we left the smooth road, on to the piste (gravel) and the small border crossing. Unfortunately the computer was down and we had to camp at the border town overnight, wasting good cycling time. About half an hour after we arrived it started to rain so heavily that the thatched roof of the little cafe where we took shelter leaked. Being the rainy season, this should be expected. The rain continued all night. There was precious little there and we helped each other pitch tents in the rain. It was a very uncomfortable night and I was most worried about the state of the road in the morning. The answer – not as bad as I imagined it might be – still wet but navigable by bicycle.

Immigration on the DRC side was hopelessly inefficient the next morning. They had been given a computer system by the British (we think) to make things more efficient, but now they use two systems – they write everything down the old way because they can’t always trust the computer to work, and they scanned our passports through the computer. They opened an hour and a half late. We crossed over into Angola, country number eleven of the expedition, and up the hill to the immigration office. There we really put a spanner in the works because we had unusual visas. Normally overland tourists can only get a five day transit visa, but we had 30 day ‘ordinary’ visas thanks to our friends in Brazzaville. They were perfectly fine about things – we just had to prove that we had enough money and be patient. Angola is a very expensive country and they wanted to know that we had allowed $US200 per person per day! Thank goodness for visa cards.

The immigration officer said he did not think I would be able to cycle to Mbanza Congo because the road would be too difficult and muddy, but after my experiences in the ROC, my vision about what can be cycled has broadened. It was only 67km through and the road was rough, muddy and very hilly like before, but I knew it was a relatively short section and we arrived in Mbanza Congo in good time. The landscape was stunning and I had really been looking forward to seeing what Angola had to offer. The regular villages were very basic and the people didn’t have much. There were no water pumps – people just collected the rain water from their rooves. The welcomes received as we passed through were overwhelmingly enthusiastic. Everyone would be shouting and kids running to catch me up – difficult to get up any speed on the rough tracks and all the time I had to focus on the surface in front of me. Of course here they all speak Portuguese so there is a new language to contend with. Simon, having spent a few years as a tour driver for Exodus in South America can speak Spanish and a little Portuguese.

Here’s some background about Angola’s history and why they have suffered 27 years of civil war:

When the Portuguese first landed in northern Angola in 1482, Mbanza Congo, with a population of 50,000 was the capital city of the Kingdom of Kongo which extended north to present day Gabon to just south of Luanda. The Portuguese gradually extended their presence in the region mainly using the populations to bolster their slave trade. In the 16th Century they sourced slaves for Sao Tome and Brazil and by the 19th Century Angola was the largest source of slaves for the Americas, including the US. A massive forced labour system continued until it was outlawed in 1961. Funded by the British, forced labour was used in the 1950’s to build three transcontinental railways, the largest of which was the Benguela railway connecting the port of Lobito (500km south of Luanda) to the copper belt of SE Belguim Congo (DRC) and Zambia through to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

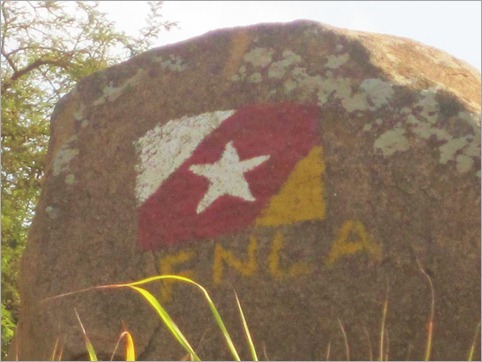

This economic development did not translate to social development. When the decolonisation process was occurring elsewhere in Africa in the 1950s, the Portuguese encouraged white immigration and intensified racial antagonisms. The Portuguese rejected independence and treated Angola like another overseas province – they held on too long. Three independence movements emerged: the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). The MPLA, which was based in the north east of the country and included Luanda, aligned itself with communist parties in Portugal, Cuba, the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries. The FNLA had links with the US and Kinshasa, DRC. UNITA connected with China and apartheid South Africa. Initially all three parties fought against the Portuguese but after the 1974 military coup in Portugal and they agreed to Angolan independence.

Disagreements over ideological differences led to armed conflict; funding and arms supplied by each party’s overseas allies. That’s the short version of how it all began. Almost continuous conflicts devastated Angola for 27 years until peace was brokered and democracy prevailed in 2002. Landmines litter the countryside killing and maiming the innocent. Many regions have been cleared but there is always a risk and this seriously affects the rural population’s ability to farm and grow food. Nearly five million people were internally displaced during the war. All but about 400,000 refugees have now returned. Angola is a country rich in oil and mineral wealth, especially diamonds. Now that the country is at peace there is a huge scramble for the national and international community to get their hands on the resources.

Heading off from the dusty, muddy streets of Mbanza Congo I was very interested to see any evidence of the conflict and how people were recovering from it. There is a whole generation who has grown up knowing of nothing but war. From Mbanza Congo we headed 230km west to reach the coast at Z’neto and then another 260km south to Luanda.

Just out of town the good road started. The Chinese are building the road all the way to Z’neto. Out of the 230km, 70km have been completed in different stages so far. The Chinese engineers seemed very friendly, always waving and often stopping to check that we were okay. Sections of jungle that they had cleared to dump their road building materials and equipment served as safe places for us to camp too. We could guarantee there would be no landmines where the land had been recently used. War in the region north of Luanda was propped up by the Soviets and so we were constantly on the lookout for evidence of it. We saw very little however, probably because Angola would like to erase this chapter of their history and move on. About half way along however, after a very steep climb there was the wreckage of a Russian helicopter which warranted inspection. Other than that, there were signs littered with bullet holes, the remnants of bridges and some buildings which had been blown up. All villages flew the national flag and sometimes a number of different ones which I have not yet identified.

As we neared the coast the savannah and rainforest changed to a drier landscape. The grasslands were lower and the forest contained many succulent species such as cacti and baobabs. A cold Antarctic ocean current circulates along the coast causing dry conditions. In southern Angola and Namibia the coast becomes desert. Many will have heard of the Skeleton Coast in Namibia. The road from Z’neto was far worse than I had anticipated. Once it had been sealed – probably before the war – but it had not been maintained in any way. The first 50km south from Z’neto had sandy patches which made the going very heavy. The bulk of the road was now unsealed but really rough with constant dips and corrugations. Zdenek did a 20km section and commented that he would have brain damage if he had to continue! I was feeling pretty rough having had to endure all this and nearly 900km in a week. I felt exhausted from the heat – my heat rash returned – and my neck felt as though it had been put through the wringer. On the second last day into Luanda the boys were a real help. After just 22km I was feeling terrible, so after that we just did 10km or 15km at a time. I would then stop for a short rest and cool off. By the end of the day we’d still managed 111km and no damage was done to the schedule. The highlight of the day was seeing monkeys playing on the road, and then again a troop watched over us as we set up camp on the little used track.

Ninety kilometres out of Luanda, we finally hit good tar road. I cycled through the fishing village of Barra do Dande and across the open grassy plains to connect with the main highway into Luanda –the capital city of about 5 million. There couldn’t be more of a contrast between arriving in Brazzaville with a police escort and Luanda, which Simon claimed was on par with driving into Bombay. The beautiful Chinese-made road stopped about 20km out of the city and the highway disintegrated into patches of dips and sand. There was a constant stream of trucks heading for the busy port, most of them being driven by Chinese. Traffic was constricted by hopeless bottlenecks of bad road and the air was thick with dust. Drivers became impatient and drove on the wrong side of the road, so I had to be aware of vehicles coming in all directions. There were sirens sounding and vehicle racing in all directions. Even though I was exhausted I had to concentrate, not panic and be very alert to remain safe. In these conditions I am quicker on my bike than the vehicle which gets stuck in traffic. I think Simon had really had enough by the time we arrived too. All this time, Dan had been trying to get instructions over the phone of where to go. I had made two contacts in Luanda. Eventually we connected with Adrian Fick through our Nando’s South Africa connection – the company he works for, AngoAlissar had invited us into the country (necessary to qualify to receive visas). Adrian has very kindly put us up in his flat, so we are very fortunate to have secure accommodation in the world’s most expensive city.

The city centre is completely different to any other African city – it is more like a Spanish city. There are cranes working around the clock, old buildings are being restored and all the cars are new. Money is everywhere in the city centre, but the cost of living makes eating out unrealistic for us. We’ve learned of the extreme levels of corruption which result in the huge discrepancy between rich and poor. In the country, there are no facilities, hospitals do not have enough medicines and people have little. In Luanda we see shops with designer clothes. The president reportedly receives a cut of every barrel of oil pumped out of the offshore rigs (2-3 million barrels per day) and is apparently the biggest land owner in Brazil. On one hand we see investment in infrastructure and every village seems to have a new school, yet I worry what will happen when the oil runs out and the Chinese will no longer be interested in building their roads (which are not made to last). The IMF has approved a huge loan to help Angola recover – I hope they can repay it.

For now we will benefit from the smooth bitumen which runs all the way down the coast to Lobito, Benguela and pretty much to the Namibian border (apart from one bad section in the mountains near Lubango). All going well it should take about 12 days to reach the border.

Comments on this entry are closed.