Title: Timbedgha to Segou

Dates: 17th-24th November GPS:

Distance: 608 km Total Distance: 2301 km

Roads: 500km of rough gravel and sand, 100km tarmac

Weather: Cooler evenings, warm days (not as hot)

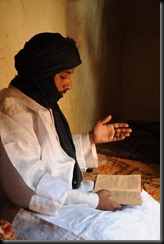

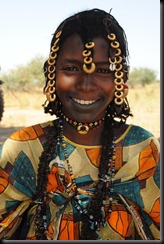

(Editor’s note: the above photo is not of Kate, of course! It’s Dan, who is Kate’s riding companion.)

I know I’ve borrowed this line from a very famous song (which was inspired by a trip to Ethiopia not Mauritania), but it is a very apt description of where we have just been in the last week or so. After Oualata, Seyid opted to stay with us (for no pay) to ensure we travelled through his country safely. Thanks to Seyid we were able to experience a part of the world which few people get to see and understand so much more about its culture and issues in a very short space of time. Of course it would have been optimum to have stayed longer, but then we would never finish the journey in the time frame I have set, and I have to always be aware of the big picture. We had planned to cycle from Nema down the more major road to Nara in Mali, but Seyid learned of a different route. If you remember, in order to reach Nema in time to meet the Governor, we had to drive the last 75km in, with the intention of returning to the exact GPS coordinate (which John had noted) to resume cycling. Our journey MUST be done in a continuous line. We actually retraced our journey even further back to Timbedgha to take a short cut through to the border. The extra attraction was that we were going to be able to visit a place called Koumbi Saleh, the once all-powerful capital of the Ghanaian empire. Twelve centuries ago, the Ghanaian empire was the most powerful in West Africa, encompassing most land – Senegal, Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger as well as Ghana itself. Even Oualata was part of the empire. This was the main attraction of taking this route, plus of course the fact that we could knock a few kilometres off and recover some lost time. The Gendarmerie (police) in Timbedgha insisted that the “road was good, with some sand but mostly firm ground”. That was the message I got anyway. Dan and I were of course a little sceptical, because they have no conception of what it is like to cycle. Our scepticism was soon justified.

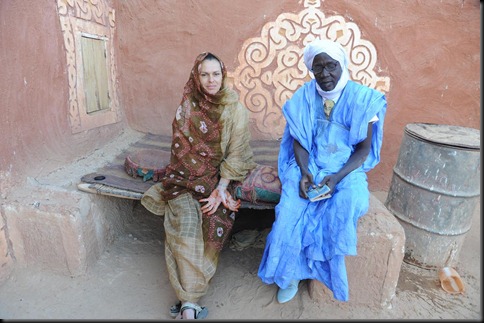

We had to wait for the gendarmerie to escort us out of town and guide us along the right path. Our Michelin map (which we have found the most reliable overall) does show a minor track joining Timbedgha to Nara, but in reality this track does not exist, rather there are just many small tracks, often evolving into a maze of alternative wheel tracks, which join up the villages. There are no directional sign posts and no signs to name the towns. It would be very easy to get lost – and we did lose our way a few times. To get through this region requires local knowledge and for someone to be able to ask for directions at each village. Many villagers would not be able to give directions, or at least certainly not accurate directions to the border. The gendarmerie from Timbedgha guaranteed that they would guide us through to the boundary of their region. They guided us for the first 15km and then kept watch over us for the next couple of days. We could not have done this section without Seyid, who not only speaks Arabic, French and English fluently, he also is a brilliant communicator and it was evident that the local people really warmed to him everywhere we went. Even right down near the border some people recognised him – or at least his radio voice as he is a well-known prolific journalist in Mauritania.

Starting off again was a real trial for me. I had been sick with diarrhoea and then a gastro for 10 days and it had taken so much out of me. I was on the mend, but had eaten nothing the day before. To add to this, we did not start cycling until 11am (heat of the day) as we had to wait for our escort to show us the way. The track, of course was just sandy wheel ruts. Out of the first 21km, there were 2km of harder-packed dirt which ran over a claypan; the rest was terrible. Off piste the over-grazed ground was covered in thorns and burrs, so while it was tempting, I did not wish to risk getting punctures. By lunch I was exhausted, overheated and feeling very negative about the “short cut”. There was no indication as to whether the track would improve, no one knew how far it was to the border and I seriously doubted whether we had made the right choice. Perhaps we should have retraced our tracks down the main road all the way back to Nioro in Mali and continued along the tarmac to Bamako and Segou. I didn’t trust the advice and didn’t think the effort and lost time could justify the visit to the ancient capital, which we knew had not been preserved. Some nomads offered us shade in their tent (open with no walls) and over a couple of hours I was able to recover and eventually agreed to keep going. Dan, who had been doing much better than me, had been risking getting punctures by cycling in the grass all morning, while I had been slogging it out in the sand. I followed his lead in the afternoon and we both trail-blazed through the often long grass, giving the thorn bushes a wide berth. By doing this we used a lot less energy, could travel faster and in fact I incurred the only puncture for the day, right in the last few kilometres which we did in the dark, trying to reach a village. We only managed 37km on day one out of Timbedgha! The chief of the village welcomed us and offered to kill a goat. Seyid accepted his offer, but the rest of us just needed simple food and sleep. I was off any local food for a few days to try and regain my health. For the next two days, Dan and I cycled almost exclusively in the grass. We discovered that there were fewer puncture-threatening burrs in the long grass, even though our progress was frustratingly tedious and slow. Setting off early on our own, we often came to unnamed intersections where the tracks forked and spent ages deliberating over which option to take. We’d mark the track in the hope that John would see the route we took.

Starting off again was a real trial for me. I had been sick with diarrhoea and then a gastro for 10 days and it had taken so much out of me. I was on the mend, but had eaten nothing the day before. To add to this, we did not start cycling until 11am (heat of the day) as we had to wait for our escort to show us the way. The track, of course was just sandy wheel ruts. Out of the first 21km, there were 2km of harder-packed dirt which ran over a claypan; the rest was terrible. Off piste the over-grazed ground was covered in thorns and burrs, so while it was tempting, I did not wish to risk getting punctures. By lunch I was exhausted, overheated and feeling very negative about the “short cut”. There was no indication as to whether the track would improve, no one knew how far it was to the border and I seriously doubted whether we had made the right choice. Perhaps we should have retraced our tracks down the main road all the way back to Nioro in Mali and continued along the tarmac to Bamako and Segou. I didn’t trust the advice and didn’t think the effort and lost time could justify the visit to the ancient capital, which we knew had not been preserved. Some nomads offered us shade in their tent (open with no walls) and over a couple of hours I was able to recover and eventually agreed to keep going. Dan, who had been doing much better than me, had been risking getting punctures by cycling in the grass all morning, while I had been slogging it out in the sand. I followed his lead in the afternoon and we both trail-blazed through the often long grass, giving the thorn bushes a wide berth. By doing this we used a lot less energy, could travel faster and in fact I incurred the only puncture for the day, right in the last few kilometres which we did in the dark, trying to reach a village. We only managed 37km on day one out of Timbedgha! The chief of the village welcomed us and offered to kill a goat. Seyid accepted his offer, but the rest of us just needed simple food and sleep. I was off any local food for a few days to try and regain my health. For the next two days, Dan and I cycled almost exclusively in the grass. We discovered that there were fewer puncture-threatening burrs in the long grass, even though our progress was frustratingly tedious and slow. Setting off early on our own, we often came to unnamed intersections where the tracks forked and spent ages deliberating over which option to take. We’d mark the track in the hope that John would see the route we took.

To the locals we may have been from outer space. One woman commented to Seyid when they were asking to see whether we had been through their village that she had seen two people moving through the grass but she didn’t know how they were travelling. She would have never seen a bicycle before! No one cycles in these parts.

We reached Koumbi Saleh by lunch on the second day. The city was once huge and well-organised, but now it was pretty much a massive pile of flat stones (slate) which was not natural in the region and would have been transported huge distances to build the city. Seyid had really done his homework, emailing academics and speaking to locals. By the time we reached Koumbi Saleh he knew the design of the city and was even able to give me a tour; the royal palace, court yard, gold chamber, mosque and army buildings. This was a major city for about 600 years. Initially they would have brought their own religion with them, but towards the end of the reign Islam was introduced and a mosque built. The locals mentioned to Seyid that a French opportunist flew his light aircraft to Koumbi Saleh about five years ago, employed some locals and ran his metal detector over the ancient gold chambers (like the bank). When the detector reacted he sent the locals away so they would not see what he found. The locals say he pilfered quite a few valuables including a sword. (I hope one day the valuables are returned, but I guess they are gone.) I understand that the site has been recognised by UNESCO, not as World Heritage as yet, but as a place of historical value. The main issue now is to preserve what is there and ensure that the local people understand its significance. The stones have been used as building material in modern nearby dwellings.

I was pretty keen to get some more distance under our belts, aware of all the time we had lost. The following day, only about 20km from the border and in the heat of the day, it was Dan’s turn to seriously doubt our route. Cycling cross country on the grass, through the burrs and being uncertain of the route through to Mali had taken their toll and Dan had had enough. He took some convincing even though we were just 20km from the border (according to the GPS). I was starting to feel stronger, although full fitness certainly not there yet. By the end of the third day we crossed the border. There was no demarcation, so John celebrated by driving his vehicle round and round in a tight circle when the GPS indicated we were there. What was incredible is that the villages changed dramatically in architecture and culture. Our last village in Mauritania was typical of what we’d seen with square mud houses, whereas across the imaginary line the next Mali village was totally different with different people, round houses and different village design. I tried to send a satellite phone podcast message at this point but unfortunately the sound quality was not fit broadcast.

The track improved a little and we could make slightly better progress to Nara, but it was still a hard slog, with a lot of sand patches and the usual head wind. There were generally more people around and more agriculture, such as fields of millet and sorghum.

We reached Nara in the dark. Unfortunately I received a puncture just as the light was fading and we were racing to reach the town. The vehicle had already gone ahead to sort out where to stay. We managed to lose each other and they came looking for us in the dark. We could see them on another track (there were so many) but could not attract their attention. Eventually we connected and pushed the bikes into town. We were able to get our passports stamped in Nara but unfortunately John had to get his vehicle carnet stamped and for that he and Daniel had to drive back up the major road towards Nema, back over the Mauritanian border, which lost us most of the next day. The main road which I had originally planned to follow was just as bad as the small tracks we’d taken. This was also the end of Seyid’s time with us. He returned with them over the Mauritanian border and then caught a lift to cover 1400km back to Nouakchott.

We reached Nara in the dark. Unfortunately I received a puncture just as the light was fading and we were racing to reach the town. The vehicle had already gone ahead to sort out where to stay. We managed to lose each other and they came looking for us in the dark. We could see them on another track (there were so many) but could not attract their attention. Eventually we connected and pushed the bikes into town. We were able to get our passports stamped in Nara but unfortunately John had to get his vehicle carnet stamped and for that he and Daniel had to drive back up the major road towards Nema, back over the Mauritanian border, which lost us most of the next day. The main road which I had originally planned to follow was just as bad as the small tracks we’d taken. This was also the end of Seyid’s time with us. He returned with them over the Mauritanian border and then caught a lift to cover 1400km back to Nouakchott.

Our route improved immensely between Nara and Sokolo. The gravel road had actually been built and was almost as good as cycling on tarmac; the exception being the last 30km into Sokolo which was horrifically corrugated (almost on par with the Tanami Track).

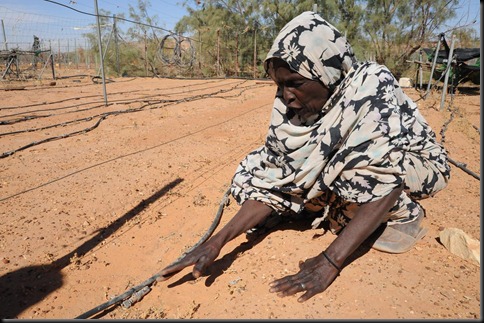

Sokolo is a real market town and signified quite a change in the journey. We had entered the Canal du Sahel region. This region contains a vast network of irrigation canals built in colonial times. Agriculture appears much more organised and is on a scale not seen anywhere on our journey so far. Our route from Sokolo to Segou via Niono was a highlight of the journey. The roads which ran alongside the canals are well maintained gravel. We cycled past rice and wheat fields and vegetable plots. Villages seemed busy and well-kept. Water pumps produced clean water. We camped near a crumbling old colonial building used as a warehouse to store flour, about 10km north of Niono. From there we knocked off the 134km into Segou on a beautiful tarmac road in very good time, eager to have a good break after a tough eight day stint.

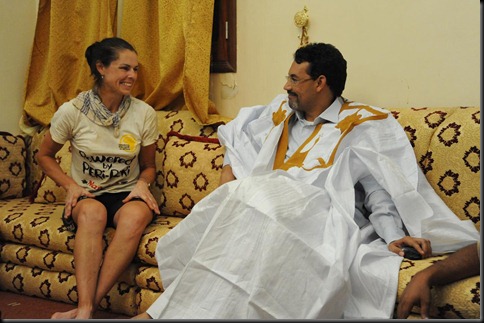

My aim in Segou is to spend time visiting the Tiby Millennium Village cluster. We’re spending three days here as a general pit stop. John and Dan have driven down to Bamako, Mali’s capital to collect bags and packages we’d had forwarded to an address there. Segou is well connected and we have a comfortable place to stay. First priority was a good meal; second was a decent shower to wash away eight days of grime, dust mixed with sunscreen.

We are a little behind schedule and plan to adjust the route slightly from the one I’ve drawn on the Google map. Our next phase will be to Timbuktu along the Niger River as planned, then we will resume our line returning to Mopti and travel east to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. This will allow us to catch up without losing the focus on the story.

Here’s a little information about Segou:

Segou (population 150,000) is the prestigious capital of the ancient Bambara kingdom, located on the banks of the Niger River. During the colonial period, it experienced strong development; it was chosen to be the center of logistics and management of the interior Niger delta region. The agricultural vocation of the Ségou region was born during this time: it is still pursued today and Ségou is located in the midst of a large agricultural zone that contains two large rice companies as well as other smaller food and agricultural industries: oil mills, dairy processing and others. The District of Segou is also home to the cluster of 11 farming communities that participate in the Millennium Village Project.

{ 4 comments }