Title: Lake Chad to Ngaoundere

Dates: 23 Jan to 2 Feb GPS:

Distance: 886km Total Distance: 6870km

Roads: Varied: perfect tarmac to steep rocky mountain climbs

Weather: Warm, dry in the far north to cool nights in the mountains

It is said that Cameroon is like Africa in miniature because it has the full complement of climatic zones; desert/Sahel near Lake Chad, savannah, mountains, coastal and tropical jungle. Cameroon also has a great range of cultures and languages. Even its colonial history is mixed. The north and east are all French colonial regions were as the south west corner was once German, then after the Second World War was taken over by the British. Our plan is to visit each of the main regions as we head south on a rather convoluted path to see what this country of roughly 15 million people has to offer.

From the Lake Chad turn-off, the rough road continued for another 50km, then I turned the corner and headed south to Waza in one big 100 mile+ day. While I enjoyed scooting along the open plains on good tarmac with a tail wind, John, Dan and Martin (our guide for ten days) diverted in to Kousseri to collect our new cameraman Zdenek Kratky fresh from the depths of a freezing European winter. (I will soon add a bio about Zdenek in the Team section of the website)

On the road we passed many convoys of UN Peacekeepers attending two different assignments. Some were off to Chad – Ndjamena, the capital of Chad is just a few kilometres from Kousseri. The others were off to mediate a border dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria. Some were based where we stayed in Waza. Our motive there was more pleasant – we spent a day visiting the Waza National Park. The park, set against the backdrop of a couple of distinctive granite hills, is highly recommended in the guide books for its range of wildlife which roam the grassy savannah plains. Fewer tourists tend to reach this isolated park. As the animals are usually best to see either in the early morning or at dusk when they come to drink at the waterholes in the cool of the day, we decided to have two excursions during these times. The Land Rover was packed with five people which included the compulsory park guide, so Martin had to stay behind for the day. We saw many animals; giraffes (which put on the best display), horse antelopes, an ostrich, deer, warthogs, jackals and many other birds. We saw lion and elephant footprints but unfortunately did not manage to spot them. There will be other opportunities later.

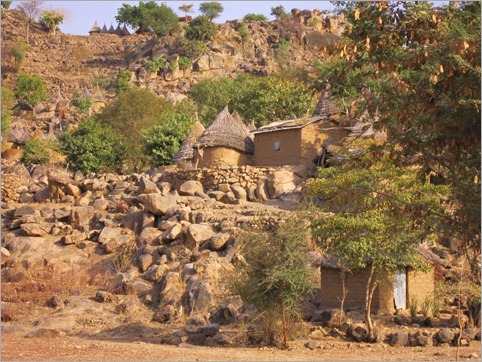

Next on the agenda were the Mandara Mountains. Sixty kilometres south of Waza, at Mora, the flat plains ended abruptly and the dry rugged Mandara Mountains dominated the landscape. For the last three months we have been travelling along the flat Sahel and so the first sign of mountains seem more spectacular. I set off alone from Mora leaving the boys trying to send emails on in impossibly slow and intermittent internet service. This can take hours so I have to prepare any messages beforehand so that when there is a rare opportunity I can at least send some messages off. The track into the mountains was a favourite. I weaved my way along the base of the passing regular villages. The dirt track was sandy at times, but not too bad, and it was good to be off the main road. The beautiful town of Koza, (a further 60km from Mora) in nestled in at the base of the mountains. The houses reminded me very much of those in the Dogon country but without the tourists. From Koza the climbing began. The next 7km was tough work with many steep inclines over a rough stony track. Many of the steep slopes are beautifully terraced to allow locals to grow their food. Just across the border in Nigeria, in the same range, UNESCO has recognised the Sukur Cultural landscape as a World Heritage site. It looks very much the same as I have described. I reached Mokolo, our goal for the day before the rest of the team. This type of stony, rugged terrain makes driving sometimes slower than cycling. We camped at the hotel to save money, however this was very convenient for Martin so he could watch the football. It seems most Cameroonians are mad keen on football (soccer) and Martin’s team was playing in the final stages of the African Cup. They lost in extra time to the eventual victors, Egypt.

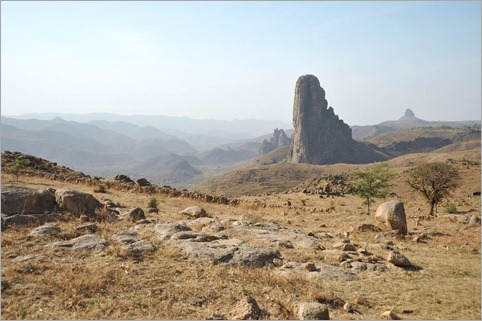

Heading south we were treated to some amazing scenery at Roumsiki in particular. The skyline is dominated with the remnants of an ancient volcano field; the cathedral-like lava plugs protruding spectacularly above all else. Conquering this landscape by bicycle is hard but rewarding work.

The road runs very close to the Nigerian border at times and much smuggling goes on. Motorbikes loaded with fuel from Nigeria (it is incredible how much they can carry on a motorbike) would often pass. Martin directed us away from the last 100km of that road to Garoua because of the level of smuggling. We turned east for 60km to Guider, back on tarmac again, visited a little known chasm called Kola Gorge, then continued along the beautiful brand new highway through Garoua, camping 40km south of the main town in the Cameroon Far North.

The land between Garoua and Ngaoundere is hilly but not so spectacular. The villages seemed quite poor, although as usual, overwhelmingly friendly. Camping in the corner of a harvested millet field, some of the villagers came to say hello – this happens just about every place we set up camp. Martin was able to find out what their lives were like. There is a general pattern emerging with what we hear. Their biggest issue is lack of water. They do not have the money and cannot find the funds to build a well for their town. They only produce just enough for themselves and cannot see how they could create funds sufficient to build their well. They believe the Cameroon government should give them the money to do so. Their women walk miles every day to get water. Most of their youth wish to leave the community to search for a more exciting life in the larger towns. We hear similar stories over and over again.

The following day was just a half day on the bike to reach Gouna. From here we drove off the main road about 100km west to the Atlantika Mountains. At Poli, 36km (2 hours drive!) we stopped to visit the Baptist pastor, a friend of Martin’s. Here we dropped off any luggage which we didn’t need for the next two days of walking, to reduce the load for the Land Rover. At last light we crossed the Faro River with the Atlantika Mountains appearing as a great wall behind silhouetted by the pink sky behind. At Wangai we were welcomed by the village chief and many potential porters. While we could have skimped on using porters, it is important to realise that this is an important source of income for them. We employed three along with the guide and set off early the next morning; one of the porters carrying an 18 kilogram bag of salt on his head for us to give the chief of the village where we were to stay that night.

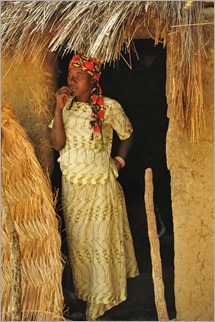

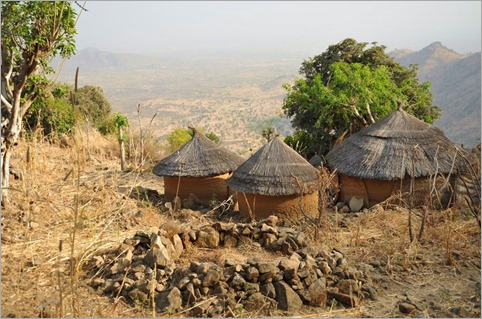

The big attractions of visiting the Atlantika Mountains are meeting the Koma people and of course the range itself which rises to about 2000 metres. The Koma only inhabit this range which straddles the Cameroon – Nigerian border. They live in isolated communities on both sides of the border where they exist self-sufficiently. The Koma don’t have access to healthcare and children don’t go to school. Traditionally they don’t wear clothes, just leaves covering their private parts (which are renewed daily). They grow and hunt for all their food and have a vast knowledge of how to use the natural vegetation for medicines. When we arrived at Librou around midday, the chief was ill and the women were opening seeds which they had collected from the cassidera tree. The seeds, which look a bit like melon seeds are pounded to make a medicinal oil used for gastric complaints. Dan and I tried them – they are extremely bitter and tasted like paracetamol. When Martin last visited seven years ago, most still did not wear clothes, but now with a stronger connection to the outside world via the missionaries, nearly all were wearing clothes in Librou, the village where we stayed. Only the chief’s wife was attired traditionally when we arrived.

After lunch and a good rest we left the bulk of our gear in Librou which is pretty much in the foothills and climbed up the steep slopes to a higher, the more isolated community called Bikeba. Here few wore modern clothes. When we arrived a man and a woman were up in a tree collecting wild figs. I tried the pea-sized fruit which was very much like a normal dried fig – very sweet. They seem to live a very peaceful existence and have a simple lifestyle with “penthouse suite” views. They live off fruit such as mangoes, papaya, wild palm trees, grow millet, maize, chickens, cows, small goats and hunt. They would regularly catch small animals such as rabbits and occasionally, perhaps once every two months trap a gazelle.

After lunch and a good rest we left the bulk of our gear in Librou which is pretty much in the foothills and climbed up the steep slopes to a higher, the more isolated community called Bikeba. Here few wore modern clothes. When we arrived a man and a woman were up in a tree collecting wild figs. I tried the pea-sized fruit which was very much like a normal dried fig – very sweet. They seem to live a very peaceful existence and have a simple lifestyle with “penthouse suite” views. They live off fruit such as mangoes, papaya, wild palm trees, grow millet, maize, chickens, cows, small goats and hunt. They would regularly catch small animals such as rabbits and occasionally, perhaps once every two months trap a gazelle.

When we returned back down the slope to Librou, the women were all traditionally dressed and ready to perform a few dances for us. Martin said that this was a great pleasure for them to perform for outsiders. That was obvious once they got started in the twilight. The men played drums and flute. All of the women got involved from the oldest grandmother to children and babies attached to their mother’s backs. After the dancing we presented them with gifts; the salt, matches and soap.

That night we set up our tents on the terraced land, washed in the stream and slept in a very different world. As we set off back towards Wangai, a few children passed us in a hurry to reach the village to go to church. We all greeted them with “tika tika” which is the only Koma word I learned, meaning hello. I wondered what would be left of the culture in a few more years.

We left Wangai and ate a picnic lunch beside the Faro River. Completely out of context with the surroundings was the 9 billion CFA (about $AUD2.25 billion) bridge spanning the river, about 500m wide. The bridge which connects two dusty rough tracks was funded by the European Union. It is a fantastic but extravagant bridge I would think for the needs of the local people. The track finishes at the Atlantika Mountains. That night Martin suggested we stay at the Catholic Mission at Fignole, about half way back to the main road. Just before our destination we stopped in a small village named Gode to shop at the market. Some people became a little upset with seeing a camera filming them and Martin tried to smooth the situation over with the village chief. I then followed and presented him with an expedition badge. A teacher by profession, the village chief was an important figure in the region – he signed his name as SA Majeste (his majesty) Haman Bangare, Lamido of Gode. Basically he is the king of the region who is in charge of 50 villages around Gode. From then on the Lamido opened up, made us feel very welcome and started to pour out all the problems in his community. Water, health and education are again the main issues. The village pump had broken six months before and now everyone had to find water out of town, often dirty, and carry it back to their homes. “Why can’t you fix the pump?” (Heard that one before – this is another ‘Oualata story’) He said the government will not give them any money and they are too poor to raise the funds. Everyone only produces enough to exist. He said the weather is changing, getting hotter and drier and so it is more difficult to produce enough food. He attributed this to global warming. The Lamido is an intelligent man and he genuinely loves his people, but he can’t see how to fix a simple hand pump. He does need help. There is only one headmaster for 50 schools which makes his task impossible. There is no hospital or even a health centre for 20,000 people. He says they are trapped in poverty and he can’t see how they can trade their way out of it. Martin says that in regions like this, near the national borders, people tend to be struggling much more than in central Cameroon. Improving infrastructure is also important but it seems to me that the $2.25billion spent on the Faro River Bridge could have been put to better use by looking after the people of the region. I promised the Lamido that I would help publicise the plight of his people by writing about it. He wrote his address: SA Majeste Haman Bangari, Lamido de Gode, Gare a Gode, Arrondissement Poli, Department du Faro, Region Nord, Cameroun. They do not have telephone or internet in Gode.

We left Wangai and ate a picnic lunch beside the Faro River. Completely out of context with the surroundings was the 9 billion CFA (about $AUD2.25 billion) bridge spanning the river, about 500m wide. The bridge which connects two dusty rough tracks was funded by the European Union. It is a fantastic but extravagant bridge I would think for the needs of the local people. The track finishes at the Atlantika Mountains. That night Martin suggested we stay at the Catholic Mission at Fignole, about half way back to the main road. Just before our destination we stopped in a small village named Gode to shop at the market. Some people became a little upset with seeing a camera filming them and Martin tried to smooth the situation over with the village chief. I then followed and presented him with an expedition badge. A teacher by profession, the village chief was an important figure in the region – he signed his name as SA Majeste (his majesty) Haman Bangare, Lamido of Gode. Basically he is the king of the region who is in charge of 50 villages around Gode. From then on the Lamido opened up, made us feel very welcome and started to pour out all the problems in his community. Water, health and education are again the main issues. The village pump had broken six months before and now everyone had to find water out of town, often dirty, and carry it back to their homes. “Why can’t you fix the pump?” (Heard that one before – this is another ‘Oualata story’) He said the government will not give them any money and they are too poor to raise the funds. Everyone only produces enough to exist. He said the weather is changing, getting hotter and drier and so it is more difficult to produce enough food. He attributed this to global warming. The Lamido is an intelligent man and he genuinely loves his people, but he can’t see how to fix a simple hand pump. He does need help. There is only one headmaster for 50 schools which makes his task impossible. There is no hospital or even a health centre for 20,000 people. He says they are trapped in poverty and he can’t see how they can trade their way out of it. Martin says that in regions like this, near the national borders, people tend to be struggling much more than in central Cameroon. Improving infrastructure is also important but it seems to me that the $2.25billion spent on the Faro River Bridge could have been put to better use by looking after the people of the region. I promised the Lamido that I would help publicise the plight of his people by writing about it. He wrote his address: SA Majeste Haman Bangari, Lamido de Gode, Gare a Gode, Arrondissement Poli, Department du Faro, Region Nord, Cameroun. They do not have telephone or internet in Gode.

We drove on to the Fignole Catholic Mission just five kilometres away, where we were greeted by Sisters Agnus (from Canada) and Laure (from Republic of Congo). The mission is set in an idyllic location at the base of the mountains beside a village. They are responsible for educating and providing for the locals. For us they provided very clean, cheap accommodation. Martin also brought us there to see human skulls from the ancient burial custom of the local Namji people. Martin found a young man who took us on a short expedition the following morning to see some of them. We walked through grass which was up to three metres high to the base of the mountain. Normally in Cameroon they burn the grass regularly to keep down ground fuel and encourage fresh growth for the animals to graze. This prevents excessive damage by wild fires to people and wildlife. Because the grass was so high we were only able to see a few examples of the skulls which the boy said were scattered throughout this region.

We drove on to the Fignole Catholic Mission just five kilometres away, where we were greeted by Sisters Agnus (from Canada) and Laure (from Republic of Congo). The mission is set in an idyllic location at the base of the mountains beside a village. They are responsible for educating and providing for the locals. For us they provided very clean, cheap accommodation. Martin also brought us there to see human skulls from the ancient burial custom of the local Namji people. Martin found a young man who took us on a short expedition the following morning to see some of them. We walked through grass which was up to three metres high to the base of the mountain. Normally in Cameroon they burn the grass regularly to keep down ground fuel and encourage fresh growth for the animals to graze. This prevents excessive damage by wild fires to people and wildlife. Because the grass was so high we were only able to see a few examples of the skulls which the boy said were scattered throughout this region.

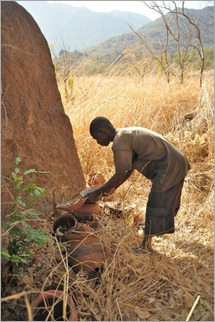

The tradition for the Namji people is that when an elderly man dies, the body is left for about a week, then placed inside a cow hide to fester for a while. When it is ready they perform a burial ceremony and bury the body. The head is wrapped in cloth like a mummy and left above ground. Later a qualified person removes the head during a special ceremony which then relocates to a site in the bush. An animal such as a cow or a goat is sacrificed and the blood is poured over the head which has been placed in a ceramic pot and closed. About once a year, the pot is revisited, another animal sacrificed and blood added. I guess this is their version of putting fresh flowers on a grave – respecting those who have passed on. Just as we were about to leave the mission we briefly met a Polish missionary who has been busy building wells in the region. When asked about the pump at Gode, his opinion was that the problem was so simple and that they should be able to source the small amount of money required to fix the pump.

The tradition for the Namji people is that when an elderly man dies, the body is left for about a week, then placed inside a cow hide to fester for a while. When it is ready they perform a burial ceremony and bury the body. The head is wrapped in cloth like a mummy and left above ground. Later a qualified person removes the head during a special ceremony which then relocates to a site in the bush. An animal such as a cow or a goat is sacrificed and the blood is poured over the head which has been placed in a ceramic pot and closed. About once a year, the pot is revisited, another animal sacrificed and blood added. I guess this is their version of putting fresh flowers on a grave – respecting those who have passed on. Just as we were about to leave the mission we briefly met a Polish missionary who has been busy building wells in the region. When asked about the pump at Gode, his opinion was that the problem was so simple and that they should be able to source the small amount of money required to fix the pump.

We revisited the pastor in Poli to collect our belongings and a spot of lunch. Then it was back to Gouna and the main road. Here Martin said goodbye. He was a terrific guide who is very knowledgeable and has become a good friend. Even since returning to his home in Maroua, Martin calls us regularly to check how we are getting on. If you need a good guide for Cameroon, particularly in the north and west, Martin is your man. Buinlemmartin@yahoo.fr; +237 750245. I did a quick 60km that afternoon and another full day on the bike to reach Ngaoundere, 1100metres above sea level, ready for a day’s rest and catch up.

{ 1 trackback }

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

We often look to the west for beauty but true beauty lies within the lands of our ancestry