Kate shares some of her amazing experiences so far on her trans-African trip in this podcast episode.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

{ 5 comments }

Kate shares some of her amazing experiences so far on her trans-African trip in this podcast episode.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

{ 5 comments }

Title: Ouagadougou to Niamey

Dates: 18th to 23rd Dec GPS:

Distance: 575 km Total Distance: 4133 km

Roads: 495km tarmac; 80km gravel, sand

Weather: mid’s 30’s during the day, cooler evenings, constant east-NE headwinds

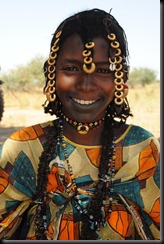

My first impressions of Burkina Faso were the friendly, slightly more understated and reserved nature of the people we met in the towns and villages as we passed through. People greeted us with a two-handed wave (rather than the usual single hand wave) which is rather difficult to reciprocate from over the handlebars! They generally seemed happy and content. Even though there is obvious poverty – Burkina is rated as the second poorest country in the world – there seemed to be construction of new roads and buildings going on just about everywhere. Burkina has benefitted from political stability since their government was democratically elected in 1987. They were one of the first Sub-Saharan countries to prepare their Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper which qualifies them for debt relief. This means they have an effective donor coordination strategy and an environment more conducive to foreign investors. In Ouagadougou we were guests of one of our sponsors, Gryphon Minerals, who themselves have been attracted by the stable economic conditions and the prospect of mining gold tenements in the Banfora region in the south west of the country. A big thank you goes to Isabelle Guirma, Pascal, Alice and Martin who took care of us in Ouagadougou.

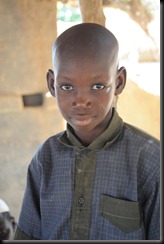

My main focus however in Burkina Faso was to look at the state of women’s and girls’ education by visiting one of Plan International’s projects in the Samentenga region approximately 100km to the north east of the capital. Traditionally in Burkina, as with most of the Sahelian countries, boys have been given priority for education – girls are expected to work, marry at an extremely young age and produce a large family. The country also sits at the bottom of the table as far as illiteracy is concerned. In 2007, 29% of adults over 15 years are able to read and write. As I discovered, some very promising sustainable changes are being made, particularly cultural changes.

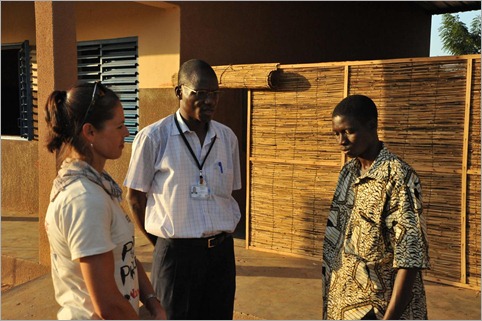

Plan International of Australia connected me with Plan Burkina and our visit was hosted by Ms Francoise Kabore and the director, Mr Oumarou Koala (And yes, we had the obligatory joke about the relevance of the director’s name to Australia). Once in Kaya, the regional capital, the three of us and a cameraman drove out to a small village where I was to be shown the new BRIGHT school. (John and Dan had stayed back in Ouagadougou to collect our visas which had needed to be extended. Paddy has gone home to Australia for Christmas.) BRIGHT stands for Burkinabe Response to Improve Girls’ Chances to Succeed. The project was initially set up by a US organisation called the Millennium Challenge Corporation. Launched in 2006, Plan International is the major stakeholder. Since then 132 BRIGHT schools have been built educating over 17,000 new primary students; more than half of which are girls.

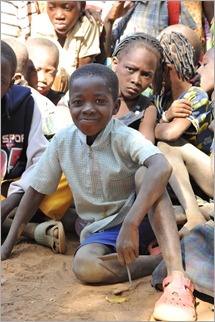

We arrived outside the school to find many of the villagers waiting to greet us. Mr Koala asked for permission from the community before we could take photos. We all introduced ourselves; Francoise translating for me. After formalities were over and we were accepted, the elders selected a group containing a representative cross section of the community to meet, answer my questions and discuss their thoughts about education and how it affects their lives. Women with their babies, elders and community members of all ages filled the largest of three classrooms. Francoise, Oumarou and I sat out the front. Here’s a summary of what we discussed:

How has the village changed in the three years since the school was built? What was it like before?

‘The school brings the community together; it gives hope for the future. Now our children have opportunities which we never had.’

One of the more outspoken men explained that he had never had the chance of education – he can’t read or write (but I complemented him on his ability to speak – he was very articulate). He said now girls are no longer expected to marry and have children when they are very young. Now they are encouraged to go to school for formal and non-formal classes. This is a big change. More girls than boys attend school here and their results are marginally better overall. (Hearing the man explain this new attitude really touched me – this is such an important cultural change)

One of the more outspoken men explained that he had never had the chance of education – he can’t read or write (but I complemented him on his ability to speak – he was very articulate). He said now girls are no longer expected to marry and have children when they are very young. Now they are encouraged to go to school for formal and non-formal classes. This is a big change. More girls than boys attend school here and their results are marginally better overall. (Hearing the man explain this new attitude really touched me – this is such an important cultural change)

How have they encouraged more girls to attend school?

Initially partners of the BRIGHT Project educated the community leaders who in turn individually spoke to each family to explain the importance of attending school. School lunches were provided for those who attend as incentive. These people are very poor and this ensures the kids get at a good meal every day.

(To the three teachers) What can be done to improve the quality of their work? What do they need? The young headmaster read out the class sizes – average of 55 students per class. Currently there are three classrooms and teachers are expected to teach two years. Their dream would be to have a classroom for each year level. Another request was really simple – ‘We need electricity so the school can have light.’ Teachers are restricted to daylight hours to prepare lessons. If there were lights, the school could then be the focus for community event after dark and students could also do their homework. A normal school day would entail starting at 7.30am, working through to lunch (I think this was 11.30am). Then they break before resuming at 3pm for the two hour afternoon session.

What are the main types of non-formal education?

There is a special program for young mothers to improve literacy as well as give practical lessons such as in agriculture. With young better educated mothers, this ensures their children have the support and encouragement they need to attend school every day.

There is a special program for young mothers to improve literacy as well as give practical lessons such as in agriculture. With young better educated mothers, this ensures their children have the support and encouragement they need to attend school every day.

(To the women) What changes and improvements would you like to see in the village over the next five years?

Water is the main issue. The village only has one well and there is just enough water for drinking (not growing things). A man who had walked from a neighbouring village said that often young girls don’t arrive at school until about 10.30am because they have to queue to collect water, then carry it some distance. Here they can only grow millet (like in much of the Sahel) because it does well in dry conditions and only has a four month growing cycle.

Another woman piped up to say that the other outstanding need is a health centre. Now they have to walk many kilometres to get medical help. She said education is good for preventing health issues, including delaying child birth until the mothers are older (and their frames ready for pregnancy and birth), but they need a health centre.

These were the main topics we discussed. We took plenty of photos after which the teachers introduced me to their students. This visit has given me much more insight into how the whole community is affected by the new school. The community is obviously very poor, but the spirit is so positive and their ideas constructive. I think, as was mentioned initially, the community is inspired by the progress made since 2006.

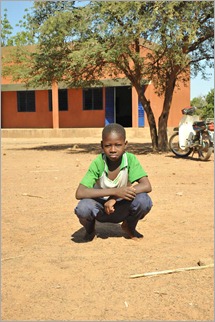

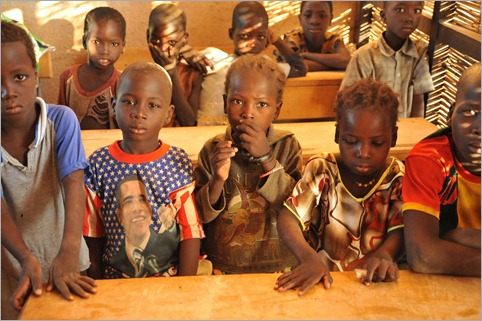

John and Daniel arrived in the early evening with visas and joined me the following morning when Francoise and Oumarou took us to another larger village to be a part of a special educational gathering being presented by a group of senior students from the secondary school. Hundreds of kids of all ages, the teachers and a few others gathered around where the young leaders were to perform and deliver their messages. Facilitated by Plan Burkina, this was designed to be a fun way to get important messages across and was a great example of child-centred development. The main message of the day was to stop violence in schools. A group of approximately twelve students, each having a few lines to say, delivered the messages, starting with (roughly) “Education is a basic human right, everyone has the right to receive an education”… If students are afraid to go to school because of violence, then this affects their learning, health, the community… On the backs of their t-shirts I could see important messages about stopping violence, dental health and education. After the main messages were performed (and this was really well done), the students invited first their teachers to individually join them the dance a little. Next there was a question and answer session where students from the audience, primary and secondary levels were asked questions. If they gave the right answer they received a little gift. At times the gift giving got a little out of control with over-enthusiastic kids and the teachers had to calm the audience down. More dancing. The second time round we all in turn were invited up – even I had to take part! To finish Mr Koala rounded everything up, also introducing me and the expedition in two languages (French and then Mossi, the local language). I was invited to say a few words which he translated.

After it was all over, I met the English teacher, Zongo Karime and encouraged him to get involved in the BTC education program. He would like to but obtaining access to the internet is difficult and expensive for him. Zongo also explained how difficult it was for him to work in the secondary school. There is effectively only one decent classroom and he has to teach classes of 130 children! Not surprisingly, he said he is burnt out. We had lunch with the teachers before saying goodbye to Francoise and Oumarou, two very impressive people, and moved on.

The region around Kaya is quite attractive, with a few ancient rocky hills – good for camping. The road to Dori was obviously brand new with regular small villages along it. I pushed on into a steady headwind as usual. Dan’s knee isn’t right yet, so he’s manning the camera. Bani is a town of note with seven small mosque ruins built on the hill overlooking the village. It was obvious that as we headed north the people, land and climate were changing. We were back into an Islamic dominated region, whereas around Ouagadougou it was mostly Christian.

The 90km route from Dori (Burkina Faso) to Tera (Niger) crossed a little-used border. We had major difficulties even finding the track out of Dori. We were told by a couple of people to follow a good gravel road towards Sebba, then there would be a sign and we should turn left after about 4km. I set off leaving John and Dan to refill and filter our water containers, cycled past the 4km sign and thought the directions must be wrong. I asked a couple of people and they sent me back to town. At the turn off I met Dan and John heading in the same direction and so we asked a few more people – all of whom all sent us down the same road. This time I’d done 6km down the Sebba road only to have to turn around again. A motorcyclist eventually set us on the right path, 4km from town. No wonder we missed it. The sign was about something completely different, not a road sign, and the inconspicuous track was marked with a small piece of tape! I’d added another 15km for nothing. Not quite what we expected for a road leading to a border crossing! The track was sandy at times, and like back on the Mauritania-Mali border, there were no road signs. It was just a case of cycling from village to village asking for directions to the village of Sitenga on the border. As these people rarely see white people, if I did stop to ask for directions the whole village would appear and it was difficult to explain that I had to keep moving on to get to Tera. This little section was another highlight.

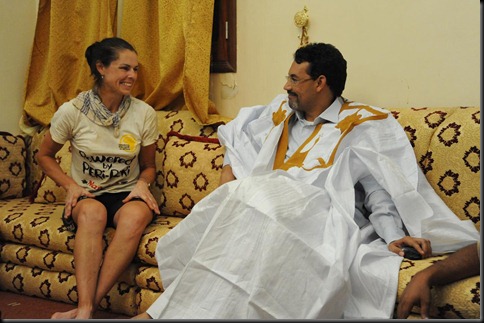

Times are about to change in this region though. A brand new road is being pushed through – on the Niger side, 40km from Tera, the newly metalled road starts. Much of it is still under construction, forbidden for vehicles to use it yet, but they didn’t seem to mind me creeping quietly over the new surface. I did another huge 100-mile day into the wind to get within reach of Niamey, Niger’s capital. At Farie we crossed the River Niger at dusk. John got there a little before me and was able to put the Land Rover on the boat, which only crosses when it is full. Dan waited behind for me. Eventually Dan and I took a pirogue across the river at last light. Ali, our main contact and fixer from another sponsor, NGM Resources, was waiting for us at Farie. There was little there, certainly no place to stay, so Ali led us down to Niamey where we have some very comfortable accommodation. The following morning we drove back to Farie and I cycled the final 60km, this time into a cruel headwind. John and Dan accompanied me for about 20km each; Dan just testing out his knee. John likes to get on the bike when possible to get some exercise – and it’s good to have his company.

So it’s Niamey for Christmas. Ali just arranged for us to see the wild giraffes about 70km south of the city. There are about 200 which co-exist with villagers in the region. Apart from a few monkeys and vultures, the giraffes are the first wildlife we’ve really seen. Over the years, the human population has grown to levels unsustainable in the Sahel and the loss of habitat has pushed out most of the wild animals.

{ 5 comments }

Title: Timbuktu to Ouagadougou

Dates: 6th – 14th Dec GPS:

Distance: 445km Total Distance: 3558km

Roads: 200km gravel, 245km tarmac

Weather: Cooler nights, daily temperatures – low 30’s

This last section started with a two day journey on a pirogue up the River Niger from Timbuktu to Mopti rejoining the cycling line at Sevare, then pushing on to the Dogon Country where we stayed in a village called Djiguibombo (pronounced Jiggiboombo). From there I cycled across the border into Burkina Faso, staying in the town of Ouahigouya before a final 190km monster day into Ouagadougou!

A visit to Timbuktu would not be complete without visiting the library, mosque and markets. In keeping with the same themes of importance as Oualata and Djenne, Timbuktu exists as a centre for Saharan trade. The Touareg (people of the desert) settled at Timbuktu as it is well placed at the most northerly point of the River Niger, where it flows through desert sands. Here desert traders can meet river traders. Camping beside the river the first settlers noticed they suffered much illness, so Timbuktu is set 18km north of the river in the dry desert sands. To find out more click on link: Timbuktu’s wonderful history.

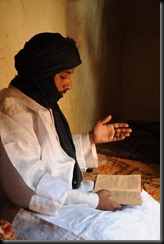

The library benefits from contributions worldwide. Compared to Oualata, the main library is beautifully kept; the manuscripts well displayed and protected in a climate controlled atmosphere away from direct light in glass cabinets. Great efforts are being made to preserve manuscripts some of which are up to 1000 years old. One of the more interesting books I thought was a 16th century manuscript outlining the rights of Islamic women – that all Islamic women have the right to spend time to make themselves more beautiful. The world’s oldest book is also on display. They don’t really know it’s age but it was rediscovered in the 11th Century. It had been stolen by the Moroccans many years before and buried underground. Timbuktu attracted some of the greatest scholars of the day, and so many manuscripts were written there as well as brought over the desert from as far away as Iraq and the Middle East. I started to wonder about whether there could be some sort of partnership formed with Oualata to preserve their treasures. I understand that the doors are open for anyone from Oualata to visit and learn about how to catalogue and preserve their books, but they need to approach Timbuktu.

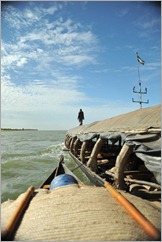

Paddy and I took a pirogue back down from Timbuktu to Mopti. Paddy had been ill so we were quarantined on the pirogue which was towed beside a larger public pinnace. John and Dan drove the vehicle back to Sevare. This was an opportunity to take a different look at life on the river and how all those who live near it rely on the Niger for everything; food, transport, water… The river is massive, often a kilometre or two wide. About 100km north of Mopti the waters disperse into Lake Beda where the normally calm waters became a little choppy. Next we entered a sea of reeds which normally lined the banks. The boats cut through a maze of channels through which we wondered how the captain navigated at night.

Paddy and I took a pirogue back down from Timbuktu to Mopti. Paddy had been ill so we were quarantined on the pirogue which was towed beside a larger public pinnace. John and Dan drove the vehicle back to Sevare. This was an opportunity to take a different look at life on the river and how all those who live near it rely on the Niger for everything; food, transport, water… The river is massive, often a kilometre or two wide. About 100km north of Mopti the waters disperse into Lake Beda where the normally calm waters became a little choppy. Next we entered a sea of reeds which normally lined the banks. The boats cut through a maze of channels through which we wondered how the captain navigated at night.

The only downside of the two day trip was that I ended up with another gastro after being served the same sauce for three meals. I was over the worst of it quickly but it did have a lasting effect for another week or so, until after Ouagadougou.

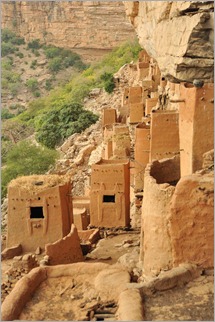

John had to do some work on the vehicle which meant we did not set out from Sevare until 3pm the following day. Our destination was the Dogon Country, Mali’s biggest tourism draw card. We knocked off the first 60km to Bandiagara in daylight. The next 21km however to Djiguibombo was in the dark; Dan and I cycling on our own for the first ten, feeling a little vulnerable without light in a strange place. Djiguibombo is set at the top of the Falaise de Bandiagara (cliff face which extends 150km, all the way up to Douentza which we visited en route to Timbuktu). It was a wonderful sight overlooking the tipi-like thatched rooftops and labyrinth of mud-walled houses in the early morning light. Dan and I coasted down to the bottom of the falaise on a spectacular 9km ride to Kani Kombole where we left our bikes and vehicle for a two day diversion on foot with our Dogon guide, Moumimi (Momo). This was the final stage of looking at the cultures of the Niger River region. Two days is just long enough to get a taste of the complex and elaborate culture. To really do it justice you could easily spend a week or two walking all the way to Douentza.

Passing a rather beautiful little mosque (mini Djenne architecture) Momo explained that Islam and Christianity (late comers in the scheme of Dogon history) co-exist with more traditional Dogon animism. Everyone respects each others’ religion bit they do not intermarry. We made a simple 4km walk to Teli. From a distance we could see a series of boxes and dwellings built into the cliff. After lunch we climbed up to explore. The boxes were an extensive series of  granary stores. Most grains these days are stored in the village at ground level and these elevated stores are only used to hold millet, sorghum and beans after a very good year. Built into the rock and in higher positions were tiny houses. Momo described these people as pygmies; the guide book calls them the Tellem people. These were the original inhabitants who lived off the fruits of the forest below. Living high up would have given them a great vantage point to defend themselves and stay safe from large predators. The Dogon believed that the Tellem could fly and had magic powers to reach them. The Tellem also used to bury the dead in their little houses. It seems more plausible that the climate a few hundred years ago was wetter and the Tellem used overhanging vines to climb to their houses. The Dogon and Bozo people arrived in the region roughly 300 years ago. The Bozo are the traditional fishermen who chose to inhabit the banks of the Niger (and still do). The Dogon arrived in the region and pushed out the Tellem so they retreated east. The Dogon cut down the forest for firewood, cultivated fields and raised animals. They basically destroyed the Tellem habitat so they could find nothing to eat. From high up the landscape is typically dry and bare and studded by regular, compact villages. Up in the cliff is the home of the Hogon, the spiritual leader. The Teli Hogon died about ten years ago. Aparently they have chosen a new one, but he is not yet ready to assume the mantle. Hogons are usually old wise men.

granary stores. Most grains these days are stored in the village at ground level and these elevated stores are only used to hold millet, sorghum and beans after a very good year. Built into the rock and in higher positions were tiny houses. Momo described these people as pygmies; the guide book calls them the Tellem people. These were the original inhabitants who lived off the fruits of the forest below. Living high up would have given them a great vantage point to defend themselves and stay safe from large predators. The Dogon believed that the Tellem could fly and had magic powers to reach them. The Tellem also used to bury the dead in their little houses. It seems more plausible that the climate a few hundred years ago was wetter and the Tellem used overhanging vines to climb to their houses. The Dogon and Bozo people arrived in the region roughly 300 years ago. The Bozo are the traditional fishermen who chose to inhabit the banks of the Niger (and still do). The Dogon arrived in the region and pushed out the Tellem so they retreated east. The Dogon cut down the forest for firewood, cultivated fields and raised animals. They basically destroyed the Tellem habitat so they could find nothing to eat. From high up the landscape is typically dry and bare and studded by regular, compact villages. Up in the cliff is the home of the Hogon, the spiritual leader. The Teli Hogon died about ten years ago. Aparently they have chosen a new one, but he is not yet ready to assume the mantle. Hogons are usually old wise men.

We walked on to Ende, Momo’s home town (population approximately 3000) where we stopped for the night. Ende has similar architecture set in the cliff face above the town. On day two we put in a decent distance; walking along the base of the escarpment, then climbed a natural chasm to Begnimato at the top. Compared to the kind of day I’d usually put in on the bike, walking 20-odd kilometres was a doddle on the cardiovascular side, but feet and knees, especially on the downhill, weren’t used to it. The slope was lush and green with overhanging vines and ficus trees. Views from the head of the chasm were spectacular. Begnimato’s setting amongst the rocks, with three individual villages (animist, Christian, Muslim) was special. After a long lunch break we started to make our way back, along the top of the escarpment to Indelou, the most amazing village we visited, then via a series of steps and laddersdown another chasm. Indelou was animist only – there was no mosque. I had the impression that of the villages we had seen, this was the most pristine – most like the original Dogon culture. In Begnimato and Indelou you can see how people use the rooves of their houses to store much of their food. It makes for an interesting and colourful patchwork.

Over the last couple of weeks we have visited Mali’s trifecta of World Heritage sites; Djenne, Timbuktu and the Dogon Country. The region is probably West Africa’s biggest attraction and the fact that they are in reasonable proximity means tourism is the major source of income. Timbuktu is obviously being hit by the security alert and the fact that the French have pulled their expats from the area. I felt tourism is being managed reasonably (I have seen much worse management). All walkers pretty much travel with a Dogon guide to get the best of the region. This is also a safeguard that groups remain small and the paths were not full of litter. Each visitor also pays a tourist tax for every village they explore so that this can help them preserve their heritage and sustain their income. Djenne also had better infrastructure, such as drains and ongoing maintenance of the mosque and streets.

The following day we said goodbye to Momo and set off towards Bankass, Koro and the Burkina Faso border. After about 40km, Dan could cycle no longer; his knee had become sore on the ride into Djiguibombo. He had kept it pretty quiet hoping he could work through it, but for quite some time he had been basically cycling with one leg. I cycled on alone – 162km that day on gravel road, all the way to Ouahigouya, then 189km the following day to reach Ouagadougou. I had to keep my wits about me and find a little more in my tired legs to negotiate peak hour traffic entering the city. Two crazy days, but it did allow us to catch up a day and give more time to organise the next complicated stages of the journey.

Of all the African cities so far, Ouagadougou seems a bit more low key and better organised. There are even cycle/motorcycle lanes which allow the traffic to flow a little better. There somehow seemed to be less pressure, yet nothing particularly remarkable to see.

In Ouagadougou we have been looked after so very well by Gryphon Minerals, one of our mining sponsors. A special thank you must go to Isabelle, Pascal, Alice and Martin for taking care of us.

Next we’re heading to Kaya and the Samentenga region north east of Ouagadougou to visit a couple of Plan International projects, concentrating on education, and in particular girls’ education.

{ 1 comment }

Title: Segou to Timbuktu (Tombouctou)

Dates: 28th Nov-5th Dec GPS:

Distance: 812km Total Distance: 3113km

Roads: 200km of rough dirt road

Weather: Approximately 30 degrees, cool nights, usual headwinds

We left Segou energised and ready to appreciate some better road surfaces. We had wanted to take a short cut closer to the River Niger all the way to Djenne, but there was no guarantee that the road was free from flooding, so we opted for the main road via Bla and San (80km longer). For the first time on the expedition I felt like we were starting to get a good rhythm and cover the distances to which I am usually accustomed – consistently 130-140km, even with a constant north easterly wind. The main road skirts the Niger River floodplain. The terrain was so flat all the way to Djenne that perhaps the highest landmarks were the giant termite mounds! Our goal was to reach the ancient town in time for the famous Monday market set in front of the Grande Mosque. After two long days in the saddle we were slightly short of the town (as we expected), marked the GPS coordinates and drove to Djenne, set on an island in the Bano River, a large tributary of the Niger.

Djenne, a town of roughly 20,000 people is most famous for its mosque, the world’s largest mud building and UNESCO World Heritage Site. Djenne is a similar age and exists for similar reasons as Timbuktu; trade and education. The town is one of Mali’s premier tourist sites. We were all up early the following day in readiness to capture the Monday market as it evolved with the morning light. We had not realised that the national holiday on Saturday continued into Monday and the bustling market never eventuated. This, of course was a little disappointing, however once I found Amadou, a very good guide, we were able to spend a good couple of hours learning about the town, the mosque and its history.

The world’s largest mud building is constantly being renovated. Before the Wet season the whole community gathers to repair the walls, adding a layer of fine mud render where required. Year after year of adding to the thickness of the walls eventually means they are too thick, absorb too much weight after the rains and collapse in places. Therefore some of the walls are being reduced in size to keep the balance. Mud for the render is mixed with rice husks to make a smooth surface whereas mud for the core of the walls is combined with straw.  Even though we had offers to enter the building (for a decent price) we respected the wishes of the Limam (head of the Mosque) and local community and elected to stay outside. Some tourists abused the privilege a few years ago so now entry is reserved for all local men and local women who have visited Mecca. Women can only enter the mosque via a special entrance around the back of the building and once inside are not permitted to even see men.

Even though we had offers to enter the building (for a decent price) we respected the wishes of the Limam (head of the Mosque) and local community and elected to stay outside. Some tourists abused the privilege a few years ago so now entry is reserved for all local men and local women who have visited Mecca. Women can only enter the mosque via a special entrance around the back of the building and once inside are not permitted to even see men.

Like Oualata and Timbuktu, Djenne has a strong tradition of education with 22 Q’uranic schools (where they are schooled in rote learning the Q’uran), many Madrassas and now government schools. A library houses ancient manuscripts.

We retraced our route to where we had stopped cycling, camped and resumed our journey towards Sevare (near Mopti). I noticed that the floodplain was more fertile and much more was being grown. A feature of the many villages was rows of grain storehouses where their staple foods are kept for use or sale. The dinky little mud huts are built off the ground to prevent moisture seeping into the grains (usually millet, rice, sorghum). They are such a contrast to how we store grains in bulk in Australia.

Sevare, a gateway to the Dogon country (more about this when we visit the unique cultural region after Timbuktu) is very well set up for tourism, with good amenities. The write up given to Mac’s Refuge by a number of guide books is well-justified and help keep Mac ahead of the competition. We have not found better food or service to date in Africa. Cycling after Mac’s special breakfast was a real challenge. My metabolism has suitably cranked up now the process obscene amounts of food. Breakfast here included: two huge buckwheat pancakes (made from millet flour) soaked in honey, numerous pieces of French toast, a large bowl of amazing homemade muesli, two helpings of fruit salad, juice and coffee.

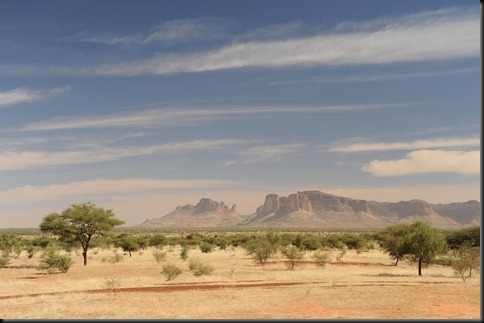

I cycled the 400km from Sevare to Timbuktu alone. Dan took over the filming for a couple of days as Paddy wanted some days off. The first day and a half, from Sevare to Douenza was an amazing, almost continuous procession of nomadic herders driving their stock, usually goats, sheep or cattle beside the road. Donkeys are real beasts of burden, hauling massive loads of firewood, grains, goats, people – just about anything. From about 50km before Douenza, the scenery on both sides of the road was special, my favourite of the journey so far. The hills which form the Falaise de Bandiagara to the south and near Douenza, a spectacular mountain range with sheer cliff faces rising to over a thousand metres.

We had heard all sorts of unfavourable reports about the road to Timbuktu from Douenza and I was up for a tussle with larger tracts of sand within the 200km. Apart from some large sand patches in the final 30km before the River Niger, the road was heavily corrugated (in fact I was shaken to bits) but manageable. I conquered the road, which had definitely been upgraded, in two days. On the second night we stayed beside a nomadic farmer, who brought us firewood and swept some ground for us to camp. We in return gave them some food – basics they probably didn’t have much of, such as sugar, potatoes, onions, rice and some tinned food.

I was amazed at the size of the Niger, Africa’s third largest river. We took the barge across, which I guess to be about two kilometres. After that there were just 18km of tarmac to reach Timbuktu. I remember my grandmother often saying “from here to Timbuktu” referring to a place which was a long or inaccessible distance away. Nowadays people can fly, drive, take a boat, walk, ride a camel…but not too many people cycle to the ancient, mystical city of approximately 50,000. Europeans didn’t make to Timbuktu until the mid-1800’s. A number were killed trying. As I arrived at the hotel where we had chosen to stay I was suddenly surrounded by press, a well-known Mali media personality and a TV camera. It took me by complete surprise. Recent kidnapping incidents in Gao, 400km away and in western Mauritania have rocked the local economy, which relies heavily on tourism. They wanted to demonstrate to the public on national and African TV that Timbuktu is safe – even a woman on a bicycle can arrive safely only experiencing friendly, helpful people (completely true). Of course we had read the alerts but also have some very reliable Touareg contacts who advised that our route is safe. John knows these people, has worked with them before and has complete faith in their advice.

I was amazed at the size of the Niger, Africa’s third largest river. We took the barge across, which I guess to be about two kilometres. After that there were just 18km of tarmac to reach Timbuktu. I remember my grandmother often saying “from here to Timbuktu” referring to a place which was a long or inaccessible distance away. Nowadays people can fly, drive, take a boat, walk, ride a camel…but not too many people cycle to the ancient, mystical city of approximately 50,000. Europeans didn’t make to Timbuktu until the mid-1800’s. A number were killed trying. As I arrived at the hotel where we had chosen to stay I was suddenly surrounded by press, a well-known Mali media personality and a TV camera. It took me by complete surprise. Recent kidnapping incidents in Gao, 400km away and in western Mauritania have rocked the local economy, which relies heavily on tourism. They wanted to demonstrate to the public on national and African TV that Timbuktu is safe – even a woman on a bicycle can arrive safely only experiencing friendly, helpful people (completely true). Of course we had read the alerts but also have some very reliable Touareg contacts who advised that our route is safe. John knows these people, has worked with them before and has complete faith in their advice.

Tomorrow Paddy and I will take a classic pirogue boat on a three day, two night trip back down to Mopti to obtain a more in depth look at life on the River Niger, the lifeline for all those who live beside it. John and Dan will drive back to Sevare, 12km from Mopti. There we will rejoin the line continuing the journey through the Dogon country and on to Ouagadougou, capital of Burkina Faso.

{ 5 comments }

Title: Millennium Village, Segou

Dates: 25th-27th November GPS:

I have been very fortunate to spend two days visiting the Millennium Villages of Tiby – a cluster of 11 villages near Segou. I have been looked after by Dr Bocary Kaya, team leader and science coordinator. I also spent time with Severin Omar, an MBA graduate working for The Millennium Promise organisation. On the first day, Bocary asked me to sit in on the annual planning meeting where the direction of the project was presented to the Millennium Village community leaders and employees to be discussed and implemented.

I have been very fortunate to spend two days visiting the Millennium Villages of Tiby – a cluster of 11 villages near Segou. I have been looked after by Dr Bocary Kaya, team leader and science coordinator. I also spent time with Severin Omar, an MBA graduate working for The Millennium Promise organisation. On the first day, Bocary asked me to sit in on the annual planning meeting where the direction of the project was presented to the Millennium Village community leaders and employees to be discussed and implemented.

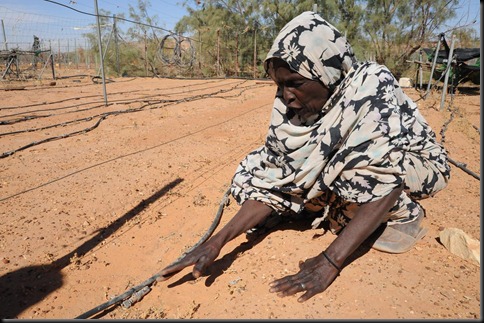

The next day Paddy and I travelled out to the villages with Sev this time to deliver onion seeds to the women working a six hectare market garden. After listening and learning for the last two days I am confident that sustainable changes are occurring and that we will not have another “Oualata situation” in Segou. Like in Potou (Senegal) this initiative has only been going for three years, however within that time there have been dramatic positive changes.

The Millennium Villages are supported and funded by a number of international organisations, however in Segou it seems that the program is being largely implemented by The Millennium Promise, an American organisation based in New York and the UN Development Program. It is also important to note that there are many stakeholders, often a number for each project which comes from international, national and local organisations and governments. While they provide funding for specific projects and control the overall direction, I find it most impressive that the whole project is being implemented and run by local Malian people; leaders, scientists, professionals.

The purpose of the Millennium Village program across Africa is to implement strategies in villages in selected vulnerable zones to ensure the Millennium Development Goals are achieved by 2015. Dr Kaya explained that while this is also the plan in Segou, they are looking at the development of the region as a whole, using advancements in science and business development to make changes sustainable. Dr Kaya has studied for his masters’ degree in Bedford, UK and earned his PhD in the US. While he could have had a successful life living and working in the US or UK, he has realised and is motivated to make more of a difference in his homeland, Mali where his education, skills and experience are so much in demand.

The meeting took place in Dioro, the largest village (approximately 20,000 people), on the banks of the Niger River, 60km north of Segou. Over about four hours the development strategy for the next year was presented by different specialists, led and facilitated by Dr Kaya. The meeting was in French, but I could get the gist of it all, made notes and was able to clarify the main details with Bocary afterwards. Infrastructure was first. Details were outlined for the improvement of roads, irrigation banks, transport, street lighting and importantly communications. In the next year there will be improvements in mobile phone reception and internet connections; communications being key to sustainable development. Food security is a big issue here with unreliable rainfall and climatic conditions not too dissimilar to what we experience in much of Australia. The river is the lifeline here for just about everything; food production (irrigation, fishing), transport, forestry. Presented were detailed plans for use of fertilisers (urea, di-ammonia phosphate) for staple crops such as millet, sorghum, rice. An artificial insemination program is being introduced to improve the standard of the herds for milk and meat production. New specifically designed milking machines will also be introduced which can process 1000 litres a day, pasteurise, pack into one litre bags, and control the temperature for storage.

The changes in the education system have been startling. Levels of literacy have increased dramatically in the region. Three years ago the average rate of literacy was around 46%, as low as 33% in some pockets. With a marked improvement in access to primary education (MDG 2 being universal primary education for all), an improved teacher to student ratio and an improved program of teacher support, literacy levels have increased to around 80%, 85% in some cases. There have traditionally been three different forms of education; government backed basic primary education (core subjects – reading, writing, arithmetic, etc.), Medersas teaching Islamic subjects and Koranic learning (rote learning of the Qur’an). Now there is a more integrated approach using these various forms of learning.

The changes in the education system have been startling. Levels of literacy have increased dramatically in the region. Three years ago the average rate of literacy was around 46%, as low as 33% in some pockets. With a marked improvement in access to primary education (MDG 2 being universal primary education for all), an improved teacher to student ratio and an improved program of teacher support, literacy levels have increased to around 80%, 85% in some cases. There have traditionally been three different forms of education; government backed basic primary education (core subjects – reading, writing, arithmetic, etc.), Medersas teaching Islamic subjects and Koranic learning (rote learning of the Qur’an). Now there is a more integrated approach using these various forms of learning.

I learned that much is being done to improve the standard of health care. Malaria has been a serious issue but now people have free access to medication. They are also able to reduce the morbidity rates for HIV/AIDS (2% in Mali), TB and childbirth. There is an education program to change the cultural practice of FGM (female genital mutilation) which is widely still practiced in many African countries. Much is being done for reproductive health care; baby kits to assist home births, medical attention for fistulas.

The last main presentation I heard was about community governance and the empowerment of women/women’s issues. My notes are by no means complete, but I learned a fair amount in one day listening to presentations in French!

Over the first three years of this Millennium Village initiative attention has been paid to all the major development topics. Now these are taking shape they are moving into the next level of development; improving science and business. I learned much from Sev the next day when we visited another smaller village to distribute onion seeds to the 243 women who work the vegetable garden. A number of different NGO’s and organisations have had a go at aiding development of the 6 hectares over the last 30 years, but all have ended up a bit like in Oualata – unsustainable. The Millennium Promise received a $US20,000 grant to change the situation, make a sustainable model which can be replicated to at least eight other viable village gardens in the area.

Sev has spent the last eight months developing the project along with his own community relations. This was the day that he finally got to distribute the seeds. Why onions you might ask? They are a vegetable which has a long storage life and as the seasonal market fluctuates the villagers can learn to store some of the produce to be sold later in the season when market prices are much higher, therefore making a reasonable profit. During the course of the year, when stocks are low, villagers are normally forced to sell off some of their staple crops (rice, millet, sorghum) to make ends meet so that by about August they are running very short on food and go hungry. By growing the onions and making more of a profit, they will not be forced to sell their staple produce and therefore avoid hunger. The initial investment involved fixing the fence and irrigation system and providing the right variety of seeds. It is important to note that the seeds are not a hand out. Once the crop is produced, the women are expected to pay back the costs with the profit. Education is given in how to maintain the economic viability – keeping the books, trading – even how to “fix the pump”. In fact, while all these initiatives are subsidised, farmers and villagers are all expected to pay it back, or at least pay for a percentage of what they receive. (everything from the milking machines to the artificial insemination program).

Believe it or not, this is just a quick overview of what I found at Tiby. These projects are such a positive contrast to what I found at Oualata, the key I think being that they are being taught the practical and business skills necessary to ensure these advancements are sustained long after the assistance has ended.

The purpose of the next phase of the expedition is to follow the course of the Niger River from Segou to Timbuktu; the river being a lifeline for the people who live beside it, for culture and development.

{ 8 comments }

Title: Timbedgha to Segou

Dates: 17th-24th November GPS:

Distance: 608 km Total Distance: 2301 km

Roads: 500km of rough gravel and sand, 100km tarmac

Weather: Cooler evenings, warm days (not as hot)

(Editor’s note: the above photo is not of Kate, of course! It’s Dan, who is Kate’s riding companion.)

I know I’ve borrowed this line from a very famous song (which was inspired by a trip to Ethiopia not Mauritania), but it is a very apt description of where we have just been in the last week or so. After Oualata, Seyid opted to stay with us (for no pay) to ensure we travelled through his country safely. Thanks to Seyid we were able to experience a part of the world which few people get to see and understand so much more about its culture and issues in a very short space of time. Of course it would have been optimum to have stayed longer, but then we would never finish the journey in the time frame I have set, and I have to always be aware of the big picture. We had planned to cycle from Nema down the more major road to Nara in Mali, but Seyid learned of a different route. If you remember, in order to reach Nema in time to meet the Governor, we had to drive the last 75km in, with the intention of returning to the exact GPS coordinate (which John had noted) to resume cycling. Our journey MUST be done in a continuous line. We actually retraced our journey even further back to Timbedgha to take a short cut through to the border. The extra attraction was that we were going to be able to visit a place called Koumbi Saleh, the once all-powerful capital of the Ghanaian empire. Twelve centuries ago, the Ghanaian empire was the most powerful in West Africa, encompassing most land – Senegal, Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger as well as Ghana itself. Even Oualata was part of the empire. This was the main attraction of taking this route, plus of course the fact that we could knock a few kilometres off and recover some lost time. The Gendarmerie (police) in Timbedgha insisted that the “road was good, with some sand but mostly firm ground”. That was the message I got anyway. Dan and I were of course a little sceptical, because they have no conception of what it is like to cycle. Our scepticism was soon justified.

We had to wait for the gendarmerie to escort us out of town and guide us along the right path. Our Michelin map (which we have found the most reliable overall) does show a minor track joining Timbedgha to Nara, but in reality this track does not exist, rather there are just many small tracks, often evolving into a maze of alternative wheel tracks, which join up the villages. There are no directional sign posts and no signs to name the towns. It would be very easy to get lost – and we did lose our way a few times. To get through this region requires local knowledge and for someone to be able to ask for directions at each village. Many villagers would not be able to give directions, or at least certainly not accurate directions to the border. The gendarmerie from Timbedgha guaranteed that they would guide us through to the boundary of their region. They guided us for the first 15km and then kept watch over us for the next couple of days. We could not have done this section without Seyid, who not only speaks Arabic, French and English fluently, he also is a brilliant communicator and it was evident that the local people really warmed to him everywhere we went. Even right down near the border some people recognised him – or at least his radio voice as he is a well-known prolific journalist in Mauritania.

Starting off again was a real trial for me. I had been sick with diarrhoea and then a gastro for 10 days and it had taken so much out of me. I was on the mend, but had eaten nothing the day before. To add to this, we did not start cycling until 11am (heat of the day) as we had to wait for our escort to show us the way. The track, of course was just sandy wheel ruts. Out of the first 21km, there were 2km of harder-packed dirt which ran over a claypan; the rest was terrible. Off piste the over-grazed ground was covered in thorns and burrs, so while it was tempting, I did not wish to risk getting punctures. By lunch I was exhausted, overheated and feeling very negative about the “short cut”. There was no indication as to whether the track would improve, no one knew how far it was to the border and I seriously doubted whether we had made the right choice. Perhaps we should have retraced our tracks down the main road all the way back to Nioro in Mali and continued along the tarmac to Bamako and Segou. I didn’t trust the advice and didn’t think the effort and lost time could justify the visit to the ancient capital, which we knew had not been preserved. Some nomads offered us shade in their tent (open with no walls) and over a couple of hours I was able to recover and eventually agreed to keep going. Dan, who had been doing much better than me, had been risking getting punctures by cycling in the grass all morning, while I had been slogging it out in the sand. I followed his lead in the afternoon and we both trail-blazed through the often long grass, giving the thorn bushes a wide berth. By doing this we used a lot less energy, could travel faster and in fact I incurred the only puncture for the day, right in the last few kilometres which we did in the dark, trying to reach a village. We only managed 37km on day one out of Timbedgha! The chief of the village welcomed us and offered to kill a goat. Seyid accepted his offer, but the rest of us just needed simple food and sleep. I was off any local food for a few days to try and regain my health. For the next two days, Dan and I cycled almost exclusively in the grass. We discovered that there were fewer puncture-threatening burrs in the long grass, even though our progress was frustratingly tedious and slow. Setting off early on our own, we often came to unnamed intersections where the tracks forked and spent ages deliberating over which option to take. We’d mark the track in the hope that John would see the route we took.

Starting off again was a real trial for me. I had been sick with diarrhoea and then a gastro for 10 days and it had taken so much out of me. I was on the mend, but had eaten nothing the day before. To add to this, we did not start cycling until 11am (heat of the day) as we had to wait for our escort to show us the way. The track, of course was just sandy wheel ruts. Out of the first 21km, there were 2km of harder-packed dirt which ran over a claypan; the rest was terrible. Off piste the over-grazed ground was covered in thorns and burrs, so while it was tempting, I did not wish to risk getting punctures. By lunch I was exhausted, overheated and feeling very negative about the “short cut”. There was no indication as to whether the track would improve, no one knew how far it was to the border and I seriously doubted whether we had made the right choice. Perhaps we should have retraced our tracks down the main road all the way back to Nioro in Mali and continued along the tarmac to Bamako and Segou. I didn’t trust the advice and didn’t think the effort and lost time could justify the visit to the ancient capital, which we knew had not been preserved. Some nomads offered us shade in their tent (open with no walls) and over a couple of hours I was able to recover and eventually agreed to keep going. Dan, who had been doing much better than me, had been risking getting punctures by cycling in the grass all morning, while I had been slogging it out in the sand. I followed his lead in the afternoon and we both trail-blazed through the often long grass, giving the thorn bushes a wide berth. By doing this we used a lot less energy, could travel faster and in fact I incurred the only puncture for the day, right in the last few kilometres which we did in the dark, trying to reach a village. We only managed 37km on day one out of Timbedgha! The chief of the village welcomed us and offered to kill a goat. Seyid accepted his offer, but the rest of us just needed simple food and sleep. I was off any local food for a few days to try and regain my health. For the next two days, Dan and I cycled almost exclusively in the grass. We discovered that there were fewer puncture-threatening burrs in the long grass, even though our progress was frustratingly tedious and slow. Setting off early on our own, we often came to unnamed intersections where the tracks forked and spent ages deliberating over which option to take. We’d mark the track in the hope that John would see the route we took.

To the locals we may have been from outer space. One woman commented to Seyid when they were asking to see whether we had been through their village that she had seen two people moving through the grass but she didn’t know how they were travelling. She would have never seen a bicycle before! No one cycles in these parts.

We reached Koumbi Saleh by lunch on the second day. The city was once huge and well-organised, but now it was pretty much a massive pile of flat stones (slate) which was not natural in the region and would have been transported huge distances to build the city. Seyid had really done his homework, emailing academics and speaking to locals. By the time we reached Koumbi Saleh he knew the design of the city and was even able to give me a tour; the royal palace, court yard, gold chamber, mosque and army buildings. This was a major city for about 600 years. Initially they would have brought their own religion with them, but towards the end of the reign Islam was introduced and a mosque built. The locals mentioned to Seyid that a French opportunist flew his light aircraft to Koumbi Saleh about five years ago, employed some locals and ran his metal detector over the ancient gold chambers (like the bank). When the detector reacted he sent the locals away so they would not see what he found. The locals say he pilfered quite a few valuables including a sword. (I hope one day the valuables are returned, but I guess they are gone.) I understand that the site has been recognised by UNESCO, not as World Heritage as yet, but as a place of historical value. The main issue now is to preserve what is there and ensure that the local people understand its significance. The stones have been used as building material in modern nearby dwellings.

I was pretty keen to get some more distance under our belts, aware of all the time we had lost. The following day, only about 20km from the border and in the heat of the day, it was Dan’s turn to seriously doubt our route. Cycling cross country on the grass, through the burrs and being uncertain of the route through to Mali had taken their toll and Dan had had enough. He took some convincing even though we were just 20km from the border (according to the GPS). I was starting to feel stronger, although full fitness certainly not there yet. By the end of the third day we crossed the border. There was no demarcation, so John celebrated by driving his vehicle round and round in a tight circle when the GPS indicated we were there. What was incredible is that the villages changed dramatically in architecture and culture. Our last village in Mauritania was typical of what we’d seen with square mud houses, whereas across the imaginary line the next Mali village was totally different with different people, round houses and different village design. I tried to send a satellite phone podcast message at this point but unfortunately the sound quality was not fit broadcast.

The track improved a little and we could make slightly better progress to Nara, but it was still a hard slog, with a lot of sand patches and the usual head wind. There were generally more people around and more agriculture, such as fields of millet and sorghum.

We reached Nara in the dark. Unfortunately I received a puncture just as the light was fading and we were racing to reach the town. The vehicle had already gone ahead to sort out where to stay. We managed to lose each other and they came looking for us in the dark. We could see them on another track (there were so many) but could not attract their attention. Eventually we connected and pushed the bikes into town. We were able to get our passports stamped in Nara but unfortunately John had to get his vehicle carnet stamped and for that he and Daniel had to drive back up the major road towards Nema, back over the Mauritanian border, which lost us most of the next day. The main road which I had originally planned to follow was just as bad as the small tracks we’d taken. This was also the end of Seyid’s time with us. He returned with them over the Mauritanian border and then caught a lift to cover 1400km back to Nouakchott.

We reached Nara in the dark. Unfortunately I received a puncture just as the light was fading and we were racing to reach the town. The vehicle had already gone ahead to sort out where to stay. We managed to lose each other and they came looking for us in the dark. We could see them on another track (there were so many) but could not attract their attention. Eventually we connected and pushed the bikes into town. We were able to get our passports stamped in Nara but unfortunately John had to get his vehicle carnet stamped and for that he and Daniel had to drive back up the major road towards Nema, back over the Mauritanian border, which lost us most of the next day. The main road which I had originally planned to follow was just as bad as the small tracks we’d taken. This was also the end of Seyid’s time with us. He returned with them over the Mauritanian border and then caught a lift to cover 1400km back to Nouakchott.

Our route improved immensely between Nara and Sokolo. The gravel road had actually been built and was almost as good as cycling on tarmac; the exception being the last 30km into Sokolo which was horrifically corrugated (almost on par with the Tanami Track).

Sokolo is a real market town and signified quite a change in the journey. We had entered the Canal du Sahel region. This region contains a vast network of irrigation canals built in colonial times. Agriculture appears much more organised and is on a scale not seen anywhere on our journey so far. Our route from Sokolo to Segou via Niono was a highlight of the journey. The roads which ran alongside the canals are well maintained gravel. We cycled past rice and wheat fields and vegetable plots. Villages seemed busy and well-kept. Water pumps produced clean water. We camped near a crumbling old colonial building used as a warehouse to store flour, about 10km north of Niono. From there we knocked off the 134km into Segou on a beautiful tarmac road in very good time, eager to have a good break after a tough eight day stint.

My aim in Segou is to spend time visiting the Tiby Millennium Village cluster. We’re spending three days here as a general pit stop. John and Dan have driven down to Bamako, Mali’s capital to collect bags and packages we’d had forwarded to an address there. Segou is well connected and we have a comfortable place to stay. First priority was a good meal; second was a decent shower to wash away eight days of grime, dust mixed with sunscreen.

We are a little behind schedule and plan to adjust the route slightly from the one I’ve drawn on the Google map. Our next phase will be to Timbuktu along the Niger River as planned, then we will resume our line returning to Mopti and travel east to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. This will allow us to catch up without losing the focus on the story.

Here’s a little information about Segou:

Segou (population 150,000) is the prestigious capital of the ancient Bambara kingdom, located on the banks of the Niger River. During the colonial period, it experienced strong development; it was chosen to be the center of logistics and management of the interior Niger delta region. The agricultural vocation of the Ségou region was born during this time: it is still pursued today and Ségou is located in the midst of a large agricultural zone that contains two large rice companies as well as other smaller food and agricultural industries: oil mills, dairy processing and others. The District of Segou is also home to the cluster of 11 farming communities that participate in the Millennium Village Project.

{ 4 comments }

Title: Oualata - Fixing the pump

Dates: 12th–15th Nov GPS:

We decided to drive the 120km to Oualata rather than cycle so we could spend more quality time there. Accompanied by an armed escort provided by the governor, the first two thirds or so of the track was similar to the Nioro road – quite cycleable. The last 30-40km was a different story – deep sand but not really any defined sand ridges. John was able to show off his driving skills as the Land Rover worked overtime through the sand pit. It certainly gave a sense of isolation. Oualata is so isolated that in Mauritania, being sent to the prison here is the equivalent to being sent to Siberia in Soviet times. Being surrounded by desert and hundreds of kilometres from anywhere, there is no escape. The first president of Mauritania, Moctar Ould Daddah, often referred to as the father of the nation and who led the country to independence from France in 1960, was toppled in 1978 in a military coup and sent to Oualata, incarcerated as a political prisoner. Since then there have been ten coups, each overthrowing a democratically elected government and a number of leaders have been sent to Oualata. The old town is nestled in the side of a rocky breakaway, the steep incline forming a natural terracing. By law all buildings in Oualata must be designed and constructed in the traditional way, with stones and ochre-brown coloured clay or dung rendering. The ruins of the old town (approximately 600 years old) sit the highest. In fact, the original town buried deep beneath the valley floor, was built in the 11th Century. Our journey ended at the mayor’s office, high up on the hillside. Here we were greeted as official guests by the deputy mayor and other commune officials. We stayed in their guest house and were treated with seemingly constant flow of communal meals and Mauritanian tea.

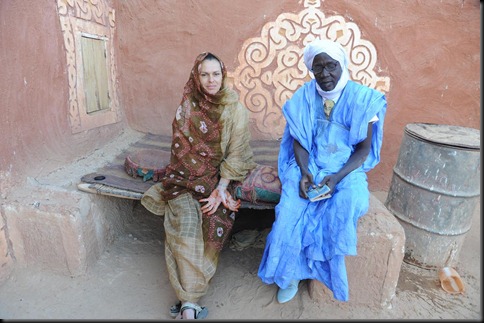

Oualata exists due to its position at the western end of a major Saharan trade route. Salt was the main material traded. The caravans would bring salt to a site a few kilometres from the town and then it was processed in Oualata. These salt caravans still exist constantly travelling the 300 or so kilometres from Timbuktu which is directly east. We have been fortunate to see two of these caravans as they arrive for their pit stop; unload, water their camels, reload and set off. Those who work the route today are descendants of families who worked centuries ago. The business is kept in the family. Many other products were also traded; materials, kola nuts, metals, slaves, food, spices, religious manuscripts and educational texts. The level of education in Oualata back in the eleventh century (before Timbuktu) was more advanced than in Europe. The deputy mayor, Baba is directly de scended from one of the four original families of Oualata. His ancestors migrated across the Sahara from Iraq, bringing their education with them. Our other hosts have similar stories; Cidina (cultural advisor and maths teacher) and Cidi Ould Merzong (general secretary of the commune and history and civic education teacher). Cidina showed us 600 year old books from his family library.

The tradition of education still exists today, although times are changing. Seyid took me to visit the Chaike (leader/traditional teacher) of the Mahadrass (Traditional school of the desert). He is in charge of teaching traditional subjects such as Islamic law, religion, languages, literature, old civilisation (Greek, Roman), history. He recited some verses only now read in Oualata and Andalucía, Spain for us. This learning process is for all stages of life from childhood to old age, the idea being that learning must be a continual process. In this culture people are encouraged to learn as it shows dignity and constant study is considered desirable. The Chaike understands the need for both his teachings and modern learning through the local primary and secondary schools. His clients are diminishing and so he needs to adapt to keep learning relevant and the community alive. Dan mentioned that as he wandered through the streets on our first day he was surprised to meet a couple of young kids – one spoke Russian, the other Spanish. Many kids are learning English and French with the hope that this will bring them opportunities away from Oualata. A whole generation is draining away from the community and with this trend the future of the town fades. The Chaike encourages the younger generation to at least try to visit their town on holidays rather than disappear forever.

The tradition of education still exists today, although times are changing. Seyid took me to visit the Chaike (leader/traditional teacher) of the Mahadrass (Traditional school of the desert). He is in charge of teaching traditional subjects such as Islamic law, religion, languages, literature, old civilisation (Greek, Roman), history. He recited some verses only now read in Oualata and Andalucía, Spain for us. This learning process is for all stages of life from childhood to old age, the idea being that learning must be a continual process. In this culture people are encouraged to learn as it shows dignity and constant study is considered desirable. The Chaike understands the need for both his teachings and modern learning through the local primary and secondary schools. His clients are diminishing and so he needs to adapt to keep learning relevant and the community alive. Dan mentioned that as he wandered through the streets on our first day he was surprised to meet a couple of young kids – one spoke Russian, the other Spanish. Many kids are learning English and French with the hope that this will bring them opportunities away from Oualata. A whole generation is draining away from the community and with this trend the future of the town fades. The Chaike encourages the younger generation to at least try to visit their town on holidays rather than disappear forever.

One of the main reasons I wanted to visit Oualata was to visit the library, designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site as a place which must be conserved for its cultural importance. The library is actually the private family collection of the Abderrahman family. The daughter being the only family member left alive, Afe Mint Abderrahman is in charge of the 1077 documents covering a broad range of subjects. While its international significance has been recognised, the cost of repairing, maintaining, and preserving the documents, some up to 600 years old, is far beyond the means of the family or the commune. Expertise in cataloguing, creating micro fiches, facsimiles, and preserving the library building is not available either. The only help has come from a Spanish NGO, Monde 3, and that ended a few years ago. This is a big, much specialised job and help is urgently required. I believe a proper management plan needs to be created first, which would be an initial appraisal, budget and plan to involve people of Oualata – those who will take ownership and care for their treasure.

One of the main reasons I wanted to visit Oualata was to visit the library, designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site as a place which must be conserved for its cultural importance. The library is actually the private family collection of the Abderrahman family. The daughter being the only family member left alive, Afe Mint Abderrahman is in charge of the 1077 documents covering a broad range of subjects. While its international significance has been recognised, the cost of repairing, maintaining, and preserving the documents, some up to 600 years old, is far beyond the means of the family or the commune. Expertise in cataloguing, creating micro fiches, facsimiles, and preserving the library building is not available either. The only help has come from a Spanish NGO, Monde 3, and that ended a few years ago. This is a big, much specialised job and help is urgently required. I believe a proper management plan needs to be created first, which would be an initial appraisal, budget and plan to involve people of Oualata – those who will take ownership and care for their treasure.

Over the generations people of Oualata have developed their own culture. In ancient times the culture was known as the Azaire culture and civilisation. They were a combination of Arab, African and Berbera – I guess this makes sense considering its importance as a focal point of Saharan trade. They had their own language. Some words which are still used will only be understood by descendants of the Azaire culture. There are also local food specialities and drinks.

I became inspired to visit Oualata a few years ago after reading a photo-story in the Geographical Magazine. A project which particularly interested me was the Women’s Farming Project, an initiative set up by a cooperation between the Mauritanian and Spanish governments. I was impressed to see photos of women from 60 of the poorest families in the town working in a newly created market garden – locally referred to as the Oualata “Garden of Eden”. Each woman was given her own plot which she took ownership of, growing vegetables from seedlings in the nursery for her family. Any excess were traded for extra income. The women were happy, empowered by a sense of purpose. I was impressed by the lushness, date palms and other fruit trees. There were solar cells and a generator to drive the water pump. It looked like a paradise in the desert. So I was shocked to see that everything was dead, bone dry and the women out of work. Why? No water. Why? The pump is broken. Why can’t you fix the pump, it’s just a simple part missing? I couldn’t really get a direct answer other than they couldn’t get any help. I didn’t understand because these are well-educated people, leaders of the town. It was only after our tour when I spoke to Seyid who had been doing some detective work to find out the real story.

The project was set up in 1994 and run for 10 years by the joint government venture. The objectives were:

In total roughly 6 million Euros were pumped into this programme.

Monde 3 took over the market gardening project, adding some tourist chalets as an extra form of income and contributed to some building and library restoration for the next two years. In 2007 the Mauritanian government reclaimed responsibility under their National Institution for Protection of Old Cities of Mauritania (Ministry of Culture).

What Seyid found out however explains what went wrong. Alongside the project, people were being given hand outs of food parcels and other basics every two weeks. This created a culture of dependency. Secondly, all skilled jobs were given to foreign hired help from Spain and Morocco (for example). There was no skill transfer, no education about management of such a project, so that when a relatively minor problem occurs such as the pump breaking down, the whole system fails – no water, no industry. I am saddened by this – a classic example of development aid in the 80’s and early 90’s. Hand outs don’t work anywhere. “Fixing the pump” in this case requires far more than attending to a minor mechanical failure. That’s just the short term emergency. All the women have the basic skills to produce the food. Even though these people are products of a culture with centuries of learning tradition, there is a desperate need to empower with managerial, operational and organisational skills. Their isolation is an issue but in modern times this can be overcome. Poverty is a problem, funds being required to restart the project, but this has to be made sustainable. From the information I have been presented, I think a possible sustainable solution could come from a partnership between an agricultural college or university and the Oualata commune. I know it is not that simple and it would require much negotiation and time to rebuild trust in foreigners offering help. I have been reminded that many have promised much to Oualata and not delivered. There is a general feeling that organisations have intervened in the past to make themselves look good in the short term rather than empowering the people of Oualata with the tools they need to sustain their way of life.

What Seyid found out however explains what went wrong. Alongside the project, people were being given hand outs of food parcels and other basics every two weeks. This created a culture of dependency. Secondly, all skilled jobs were given to foreign hired help from Spain and Morocco (for example). There was no skill transfer, no education about management of such a project, so that when a relatively minor problem occurs such as the pump breaking down, the whole system fails – no water, no industry. I am saddened by this – a classic example of development aid in the 80’s and early 90’s. Hand outs don’t work anywhere. “Fixing the pump” in this case requires far more than attending to a minor mechanical failure. That’s just the short term emergency. All the women have the basic skills to produce the food. Even though these people are products of a culture with centuries of learning tradition, there is a desperate need to empower with managerial, operational and organisational skills. Their isolation is an issue but in modern times this can be overcome. Poverty is a problem, funds being required to restart the project, but this has to be made sustainable. From the information I have been presented, I think a possible sustainable solution could come from a partnership between an agricultural college or university and the Oualata commune. I know it is not that simple and it would require much negotiation and time to rebuild trust in foreigners offering help. I have been reminded that many have promised much to Oualata and not delivered. There is a general feeling that organisations have intervened in the past to make themselves look good in the short term rather than empowering the people of Oualata with the tools they need to sustain their way of life.

I was shown a few other bright lights, small businesses looking for connections but not sure how to go about it. The tourist season is fairly short here – essentially the winter – December, January, February. With bandits infiltrating occasionally across the Algerian border, the police are vigilant with security to protect visitors and the local economy. This doesn’t help the tourist industry – it just takes one negative press report and that’s enough to stop many intrepid travellers. We stayed in a great auberge on the last two nights run by Ba o Bechir Gamny (+222 711 32 530) and there are four more. The service was amazing and his food the best we have had in Africa so far. I also met with Fatimetou Zahra Moulaye Ely president of the Women’s cooperative for the restoration of the Oualata murals and Handicrafts (loosely translated) (+222 445 67 23). Traditional artwork which is such a feature of the architecture of Oualata is done a special style of finger painting done by the women. They also make all sorts of handicrafts and beautiful cloth which they sell during the tourist season and to traders who visit the town. There would be a great opportunity for trade via internet (I’m sure not far away).

There is so much here that three days isn’t enough time to take everything in. We will move on tomorrow after visiting the salt caravans, our next stop Segou, Mali. Please be aware that this is only what I’ve learned while I am here and what Seyid has translated.

(Editor’s note: Don’t forget to visit Kate’s Diary to read about her other recent adventures, including her trek from Mali to Mauritania.)

{ 7 comments }

Title: Kayes (Mali) – Nema (Mauritania)

Dates: 5th-11th November GPS:

Distance: 653 km Total Distance: 1693 km

Roads: 140 km unsealed roads

Weather: dry, 35-40 degrees

Like when leaving St Louis, Dan and I set off unsupported for two days leaving Paddy to try to sort out his technical problems. We cycled past the many impressive old colonial buildings and market of Kayes, Mali’s first capital, over the Senegal River for the last time north east towards Sandere and Nioro du Sahel. The team was supported in Kayes (and will be again in Bamako) by SGS Laboratories and we thank Firmin Bado in particular for looking after us. It is really important that we can have such bases at strategic places on our journey to be able to catch up with everything. Over the next few days our route carved back up through the latitudes from a wetter climate which supports impressive stands of baobabs and other large trees, through the Sahel, dry and overgrazed and finally into the desert. This diversion to visit Oualata in Mauritania adds a further 700km to the route. I have also been careful not to commit to travelling through south eastern Mauritania without ensuring our safety. I’ve enlisted the help of Seyid Ould Seyid, a well-known journalist and fixer. Seyid has contacted the regional governor who is impressed by the purpose of the expedition and that we are making such an effort to visit his country and guaranteed our safety.

For the first day and a half we followed the main road, into the wind as usual, up and over small range. Actually we followed the road a bit too long, missing the turn-off to the Nioro Road (easily done as there was not an obvious road or sign posts) and covering an extra 30km in the wrong direction. Very annoying! We thought we should be able to take a short cut back to the right track on a small road shown, but the local villagers said it was basically impossible to find the route.